Transposition of the great arteries (TGA)

Transposition of the great arteries is the second most common congenital heart defect associated with cyanosis. In this congenital heart defect, the two large arteries of the heart—the aorta and the pulmonary artery—are reversed (i.e., “transposed”). This is a life-threatening malformation that must be treated immediately after birth.

Definition

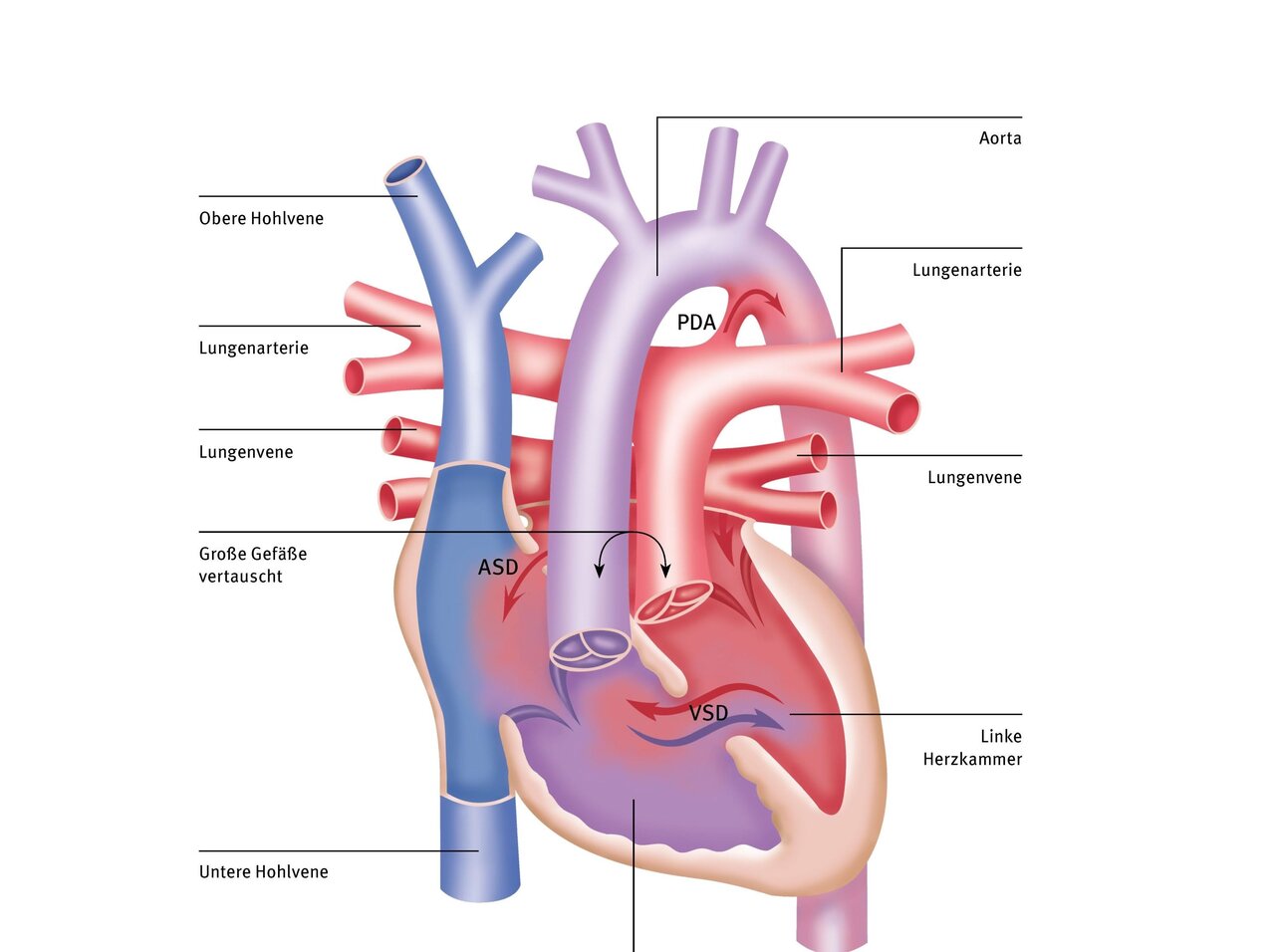

Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) refers to the incorrect position of the two large vessels, i.e., the aorta and the pulmonary artery are incorrectly positioned in relation to each other and to the pumping chambers of the heart from which they originate. There are different variants of this transposition: total transposition, partial transposition, or corrected transposition. Patients may also suffer from another heart defect.

Below, we describe total transposition. In this form of the disease, the origins of the two large vessels are reversed. The aorta originates at the point where the pulmonary artery is located in a healthy heart, i.e., from the right ventricle. Conversely, the pulmonary artery originates from the left heart.

The remaining structures of the heart are normally formed and have no further abnormalities, which is why it is also called “simple transposition,” although in this case, too, patients must be treated in a specialized pediatric cardiac clinic immediately after birth. The children are born on time and appear normal. However, their skin turns blue within the first few hours of life.

Causes

To date, no typical structural changes in the chromosome have been identified for d-TGA. Spontaneous mutations are believed to be responsible for the disease. The genetic risk for children of parents with transposition of the great arteries or for affected siblings is low and cannot be expressed as a percentage, as there are only a few case reports available.

In addition, there are reports of an increased incidence in cases of maternal diabetes mellitus, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, and malnutrition.

Consequences

In a normal heart, oxygen-rich blood flows from the lungs into the left atrium and ventricle, and from there is pumped through the aorta into the entire body, supplying it with oxygen. This produces oxygen-poor blood, which then flows back into the right atrium and right ventricle and is pumped through the pulmonary artery into the lungs to be re-oxygenated. This means that the pulmonary circulation and the systemic circulation are connected in series, i.e., “one after the other.”

In transposition, however, the venous blood enters the right atrium and right ventricle, but then returns to the systemic circulation via the aorta without flowing through the lungs and being enriched with oxygen. This leads to oxygen deficiency in the blood. Instead, the blood from the lungs returns via the left atrium and left ventricle through the pulmonary artery to the lungs. This creates two separate circulatory systems that are not connected to each other – as a result, the child does not get enough oxygen.

Only a small flow into the left heart and from there into the lungs is still possible because the small natural connection between the two atria remains open. This is the only connection between the two circulatory systems. However, in most cases, the amount of oxygen transported through this small hole is not sufficient for survival. Therefore, total transposition is life-threatening for these patients. Shortly after birth, the children are already in critical condition and urgently need pediatric heart surgery.

Diagnosis

Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) can best be detected by echocardiography (heart ultrasound). The condition can often be detected during pregnancy.

Therapy

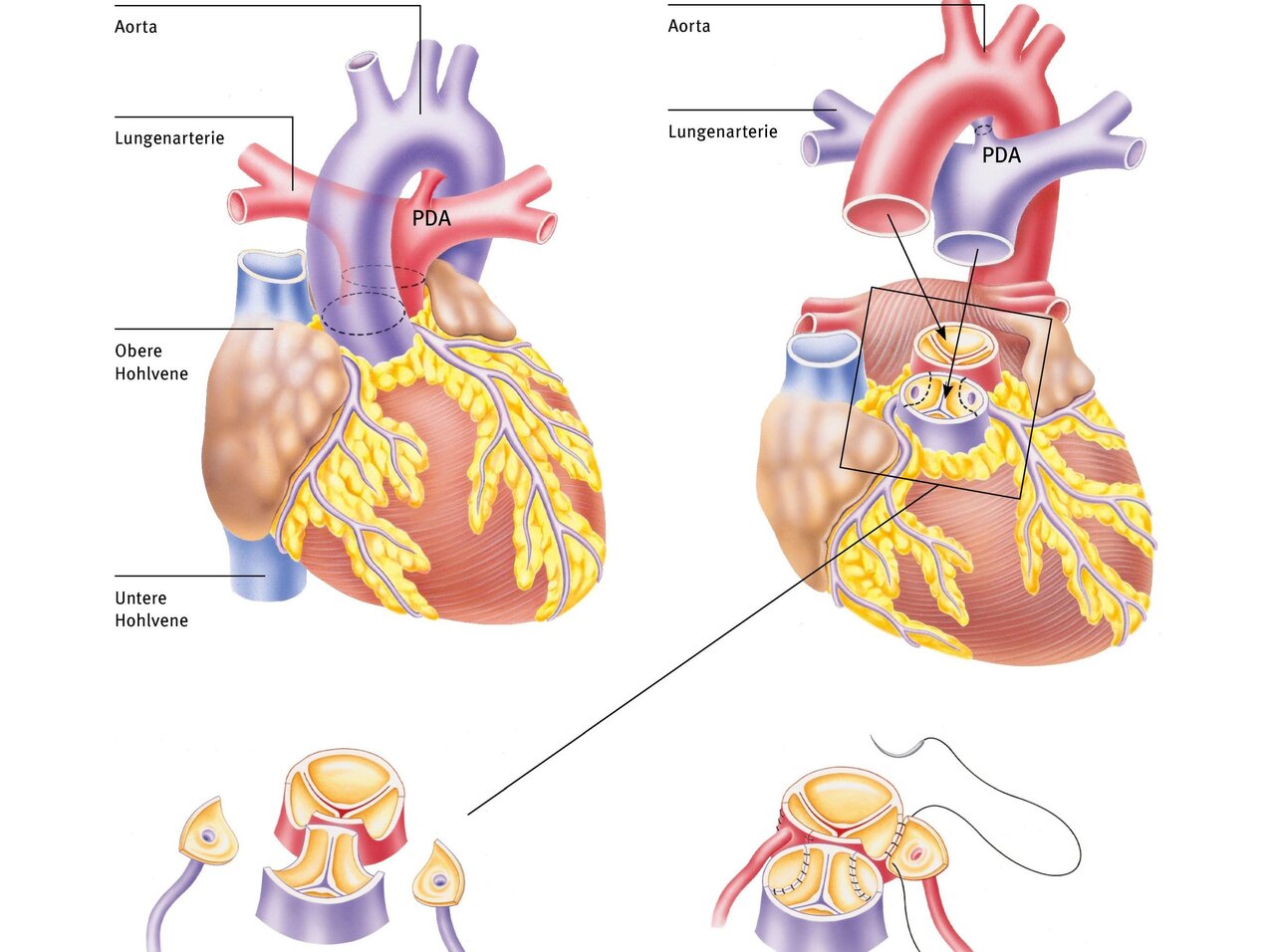

The first step is to enlarge the small hole between the atria in order to increase blood flow to the lungs. This is usually achieved with a cardiac catheter procedure (Rashkind maneuver). This involves inserting a catheter with a balloon through the hole, which is then inflated to enlarge the hole. This procedure usually has to be performed as an urgent emergency. Enlarging the hole and thereby increasing blood flow to the lungs improves the child's condition and allows time to plan the operation.

The gold standard for treating transposition of the great arteries is anatomical correction. This involves the surgical relocation and connection of the aorta to the “own” left ventricle and the pulmonary artery to the “own” right ventricle. The aorta and pulmonary artery are moved to their correct positions. This procedure is usually performed within the first one to two weeks of life.

After opening the chest, the patient is connected to a heart-lung machine, which takes over heart and lung function for the duration of the procedure. At the same time, the body is cooled externally and the blood is cooled in parallel on the heart-lung machine. Cooling significantly reduces oxygen consumption in all organs, which offers protection against possible postoperative complications.

During the operation, the transposed large arteries are severed and reattached in the correct position. To do this, the vessels must be exposed and the PDA severed. It is crucial that the origins of the coronary arteries are moved together with the aorta so that the heart muscle is also supplied with oxygen-rich blood. These small vessels are separated from the wall and then reattached to the transplanted aorta. The sites where the coronary vessels were removed are filled in with patches. The pulmonary artery is then moved in front of the aorta so that the vessels can be reattached to each other. This operation is called an arterial switch operation.

Many heart surgeries can only be performed on a stopped heart. A heart-lung machine takes over the function of the heart and lungs during surgery.

The DHZC has twelve modern heart-lung machines at its disposal, three of which are specifically designed for infants and young children.

Therapy at the DHZC

The heart-lung machine with the world's smallest filling volume gives us many opportunities to perform this complicated operation on newborns without using donated blood, which has significant advantages for the babies. Not only does this allow us to minimize the risks of infection and intolerance, but it also often enables our little patients to recover more quickly after surgery.

About pediatric heart surgery at the DHZC

Diagnostic cardiac catheterization at the DHZC

In two specially equipped and state-of-the-art cardiac catheterization laboratories of the Clinic for Congenital Heart Defects – Pediatric Cardiology we examine and treat newborns, infants, children, and adolescents of all ages with congenital and acquired heart diseases, as well as all adults with congenital heart defects. As a supraregional center of excellence, we specialize in invasive cardiological diagnostics and interventional therapy for patients with congenital heart defects. Interventional treatments in the cardiac catheterization laboratory increasingly complement or replace surgical procedures and are crucial in determining the optimal therapy for patients. Our team has many years of experience and expertise.

Questions and answers for parents (FAQ)

After the operation, your child can resume normal activities without risk. In some cases, medication may be necessary upon discharge.

Regular and lifelong check-ups by a doctor specializing in congenital heart defects are necessary.

Long-term results show that children generally develop normally.

Several studies on long-term outcomes involving large numbers of patients show that the coronary arteries grow with the graft and only five to nine percent of patients require repeat surgery.

Very rarely (in two to five percent of cases), aortic valve insufficiency occurs, leading to valve replacement.