Pulmonary valve replacement

In many cases of heart defects, pulmonary valve replacement is necessary due to severe narrowing (stenosis), leakage, or absence of the pulmonary artery. Replacing the valve counteracts the strain on the heart caused by excessive pressure and/or volume.

The pulmonary valve can be replaced using a minimally invasive procedure via a cardiac catheter or surgically. There are now numerous different valve models and treatment methods available.

Indication

When is pulmonary valve replacement necessary?

In the vast majority of cases, these are patients with residual findings after correction of a congenital heart defect with malformed pulmonary valve (e.g., Tetralogy of Fallot) or a missing pulmonary valve (e.g., truncus arteriosus communis, pulmonary atresia). In rare cases, patients with isolated pulmonary valve stenosis or insufficiency also require pulmonary valve replacement.

Follow-up procedures after previous pulmonary valve replacement, in which the old valve that no longer functions properly must be replaced, are steadily increasing due to the growing number of adult patients with congenital heart defects (EMAH). In rare cases, both valve dysfunctions (stenosis/insufficiency) can also occur as a result of balloon dilatation of the pulmonary valve, infection of the valve (endocarditis), or as a consequence of an inflammatory autoimmune reaction of the body (rheumatic fever).

Physical consequences

What does this mean for the heart and circulation?

Normal heart

In a normal heart, oxygen-poor blood flows from the body via the right atrium into the right ventricle and is pumped from there through the pulmonary artery into the lungs without obstruction. In this situation, the heart can easily overcome the resistance offered by the pulmonary vessels. The correct closing function of the pulmonary valve retains the blood column in the pulmonary artery while the right ventricle fills with new blood before the next heartbeat. In this situation, the heart can take in and eject exactly the amount of blood that the body currently needs. The capacity of the right ventricle and the wall thickness of the heart muscle required to pump this volume into the lungs remain in a clearly defined balance.

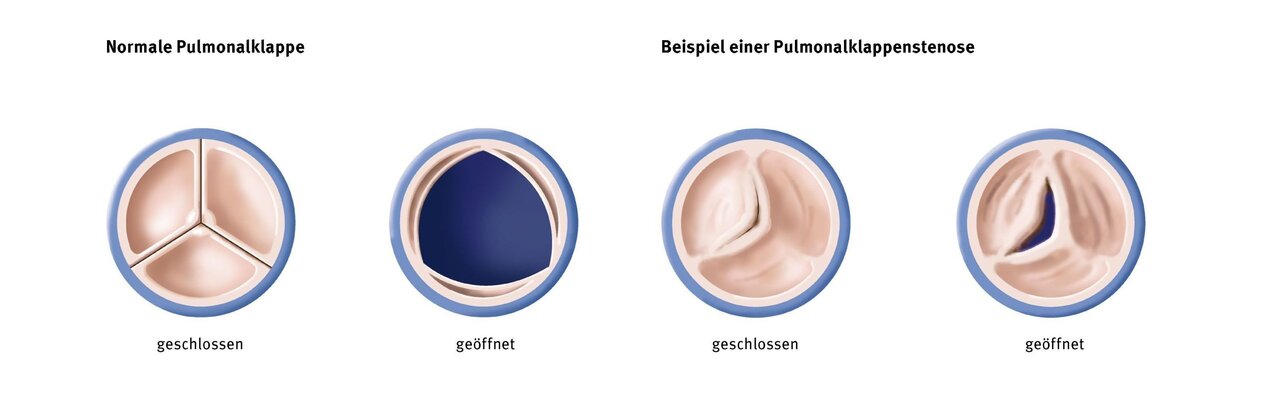

Pulmonary valve stenosis

If the pulmonary valve does not open completely or the valve ring is too small (stenosis), the right ventricle has to fight against unnecessarily high resistance with every heartbeat. In order to be able to perform this extra work, the mass of the heart muscle increases steadily. At a certain point, the system becomes unbalanced and the existing coronary vessels can no longer supply the muscle mass with sufficient oxygen-rich blood. The heart muscle loses strength and endurance. Symptoms such as palpitations, fatigue, shortness of breath, or a drop in performance can now occur, especially under stress.

Pulmonary valve insufficiency

A disturbance in the closing function of the pulmonary valve (insufficiency) leads to a permanent overload of blood volume in the right ventricle. At the end of each heartbeat, this blood flows back into the heart instead of into the lungs. The ventricle becomes larger and larger in order to accommodate this volume and increase its pumping power. Once the threshold for this compensation is exceeded, the ventricle can no longer effectively eject the additional volume. Especially under stress, this volume is now lacking to supply the muscles and organs with oxygen-rich blood. Symptoms such as fatigue, lack of motivation, and palpitations occur.

Symptoms

What does this mean for my child?

Depending on the prevailing mechanism of valve dysfunction, the severity of the impact on circulation, and the strain on the body, symptoms ranging from heart failure to shortness of breath may occur sooner or later.

Newborns and infants with severe stenosis usually require surgery within the first six months of life to correct the heart defect. The burden on the heart caused by the severely narrowed valve must be relieved immediately before persistent cyanosis, heart failure with cardiac arrhythmia, or organ damage occurs.

The heart defects that often accompany this condition are usually operated on at the same time. If stenosis and/or insufficiency of the pulmonary valve occurs as a result of a previous operation or intervention, most patients have only mild symptoms and these only become noticeable later in life. As a rule, their condition and symptoms must be monitored throughout their lives.

If there are indications of severe stenosis or insufficiency, underdevelopment, or reduced exercise capacity, a step-by-step approach is usually initiated. Measures such as drug treatment, balloon dilatation of the valve via cardiac catheterization, and even valve surgery can be combined to maintain the function of the right ventricle for as long as possible. If the valve leaks, the effect on the size and function of the right ventricle is checked regularly. If the pressure and volume load on the heart exceeds specified thresholds, further surgery or intervention is indicated. Replacement of the pulmonary valve may be necessary.

Replacing the pulmonary valve via cardiac catheterization is a minimally invasive, gentle treatment method for patients. State-of-the-art valve models adapt to the patient's anatomy by unfolding themselves after insertion into the body.

Treatment procedures

Replacement of the valve via cardiac catheterization

There are now various minimally invasive procedures for replacing the pulmonary valve using a cardiac catheter. These procedures use easily implantable, self-expanding valve replacement systems that adapt to the patient's anatomy.

New technology enables gentler treatment

A new Harmony valve prosthesis now enables catheter-assisted valve replacement for the first time, even for larger diameters – up to 38 mm. This significantly expands the treatment options, as previous catheter-based systems were not suitable for many patients due to their anatomical conditions. The prosthesis is based on a nitinol alloy with “shape memory” that adapts to the anatomical structures. Implantation is performed via a catheter inserted through a small puncture in the groin. This method allows for faster recovery compared to open surgery.

The patient's condition is monitored regularly. If the strain on the heart increases again, further interventions, including surgical valve replacement, may be necessary.

Surgical replacement using standard methods

For children and adolescents, there are various options for restoring valve function through surgical valve replacement:

- Biological valve replacement procedures (valves of human or animal origin) have the advantage that long-term treatment with blood-thinning medication is not necessary. However, biological valve replacement has a limited lifespan. As a rule, such valves must be surgically replaced again after about five to ten years.

- Alternatively, the heart valve can be replaced with a mechanical prosthesis. Following this procedure, patients must take blood-thinning medication for the rest of their lives, which increases the risk of bleeding and thrombosis in the long term.

Any type of valve replacement with a prosthesis (biological or mechanical) has the disadvantage of lacking growth potential, meaning that these options can only be used effectively once the patient has reached adult size, or frequent valve replacements due to growth must be expected.

Surgical replacement with a cell-free human valve (homograft)

In this variant, a cell-free human valve is used as a replacement. A pulmonary artery valve (pulmonary valve) is removed from the donor under sterile conditions (e.g., as part of an organ donation or heart transplant). This valve is then stripped of all donor cells using a chemical process. The removal of the cells is intended to produce a particularly durable valve. Patients with cell-free human valves do not need to take blood-thinning medication.

Current clinical studies show that the durability of these valves is comparable to that of other models. No scientifically reliable statements can be made about the possible long-term benefits at this time, as cell-free valves have not yet been used for as long as standard valves.

Treatment at the DHZC

Minimally invasive pulmonary valve replacement via cardiac catheterization

In two specially equipped and state-of-the-art cardiac catheterization laboratories at the Clinic for Congenital Heart Defects – Pediatric Cardiology, we examine and treat newborns, infants, children, and adolescents of all ages with congenital and acquired heart diseases, as well as all adults with congenital heart defects. As a supraregional center of excellence, we specialize in invasive cardiological diagnostics and interventional therapy for patients with congenital heart defects.

The DHZC is also a reference center for interventional pulmonary valve replacement. We use state-of-the-art valves that are easy to implant, unfold in the body, and thus adapt to the patient's anatomy. This enables us to offer our patients minimally invasive, particularly gentle treatment. The valve models used at the DHZC include Melody, Sapien, Venus-P, and Harmony Valve.

More about the cardiac catheterization laboratory

The DHZC 2025 is one of only two centers in Europe to be designated a Center of Excellence for the implantation of the Venus P-Valve. The Venus P-Valve is a modern, catheter-based procedure for replacing the pulmonary valve. nbsp;This innovative valve was developed specifically for patients with very large anatomical conditions in the right heart – a common consequence of surgical correction of congenital heart defects. For this patient group, the Venus P-Valve offers a minimally invasive treatment alternative that reduces pressure on the right heart, improves heart function, and can sustainably improve quality of life.

The DHZC has been recognized as a Center of Excellence for the implantation of the Venus P-Valve. Only specialized institutions that can demonstrate extensive case numbers, structured treatment processes, excellent clinical results, and a high level of scientific exchange are considered Centers of Excellence.

The Clinic for Congenital Heart Defects – Pediatric Cardiology has been certified as a supraregional EMAH center for the care of adults with congenital heart defects (EMAH) since 2011. Our center is one of the leading EMAH centers worldwide. We accompany and treat patients with congenital heart defects from their teenage years into old age. We have all modern diagnostic and imaging procedures at our disposal.

More about the DHZC's EMAH center

Surgical pulmonary valve replacement

The routine use of our heart-lung machine with the world's smallest filling volume makes it possible in the majority of cases to perform surgery without transfusion of donor blood, which has considerable advantages. This not only minimizes the risks of infection and intolerance, but also often allows our patients to recover more quickly after surgery.

The implantation of a cell-free human pulmonary valve (homograft) is increasingly being offered at the DHZC for school-age children and adolescents. The aim is to reduce late calcification and valve failure and to prevent or delay frequent reinterventions. Most patients can be extubated very early postoperatively (fast-track concept) and recover quickly from the operation.

Many heart surgeries can only be performed on a stopped heart. A heart-lung machine takes over the function of the heart and lungs during the operation.

The DHZC has twelve modern heart-lung machines at its disposal, three of which are specifically designed for infants and young children.

Questions and answers for parents (FAQ)

After the operation, your child can usually resume normal activities.

Regular and lifelong check-ups by a doctor specializing in the treatment of patients with congenital heart defects (EMAH) are necessary. Depending on the valve prosthesis used and any residual findings, medication may be necessary in individual cases upon discharge from the hospital. With mechanical valves, lifelong use of blood-thinning medication is mandatory.

Long-term results show that normal development can generally be expected. The resilience of patients with mild to moderate findings may be normal. Static endurance sports and competitive sports should be avoided in cases of moderate stenosis or worse. Depending on the severity of the findings, life expectancy may be reduced, primarily due to complications of heart failure, repeated necessary operations, and the risk of cardiac arrhythmias.

When mechanical prostheses are used, the quality of life may be significantly impaired by frequent check-ups, an increased risk of injury, and lifelong anticoagulation therapy. The incidence of thromboembolic complications (clot formation) after mechanical pulmonary valve replacement in children is 0.5–1% per patient year.

After 10 years, depending on the age of the person at the time of surgery, up to 80% of patients may not require further surgery after surgical pulmonary valve replacement. The smaller the valve prosthesis used, the greater the need for re-intervention, which affects younger children more often than young adults.