Coronary heart disease (CHD)

In coronary heart disease (CHD), the coronary arteries, which supply the heart muscle with oxygen-rich blood, are calcified. If this calcification causes constrictions or blockages, the blood flow to the heart muscle is impeded accordingly. Significantly narrowed vessels can trigger the feeling of chest tightness (angina pectoris) during physical exertion. If a coronary vessel suddenly closes completely, a heart attack is the result.

CHD can lead to secondary diseases such as heart failure or cardiac arrhythmia. The symptoms and the risk of secondary diseases can be reduced through individualised treatment.

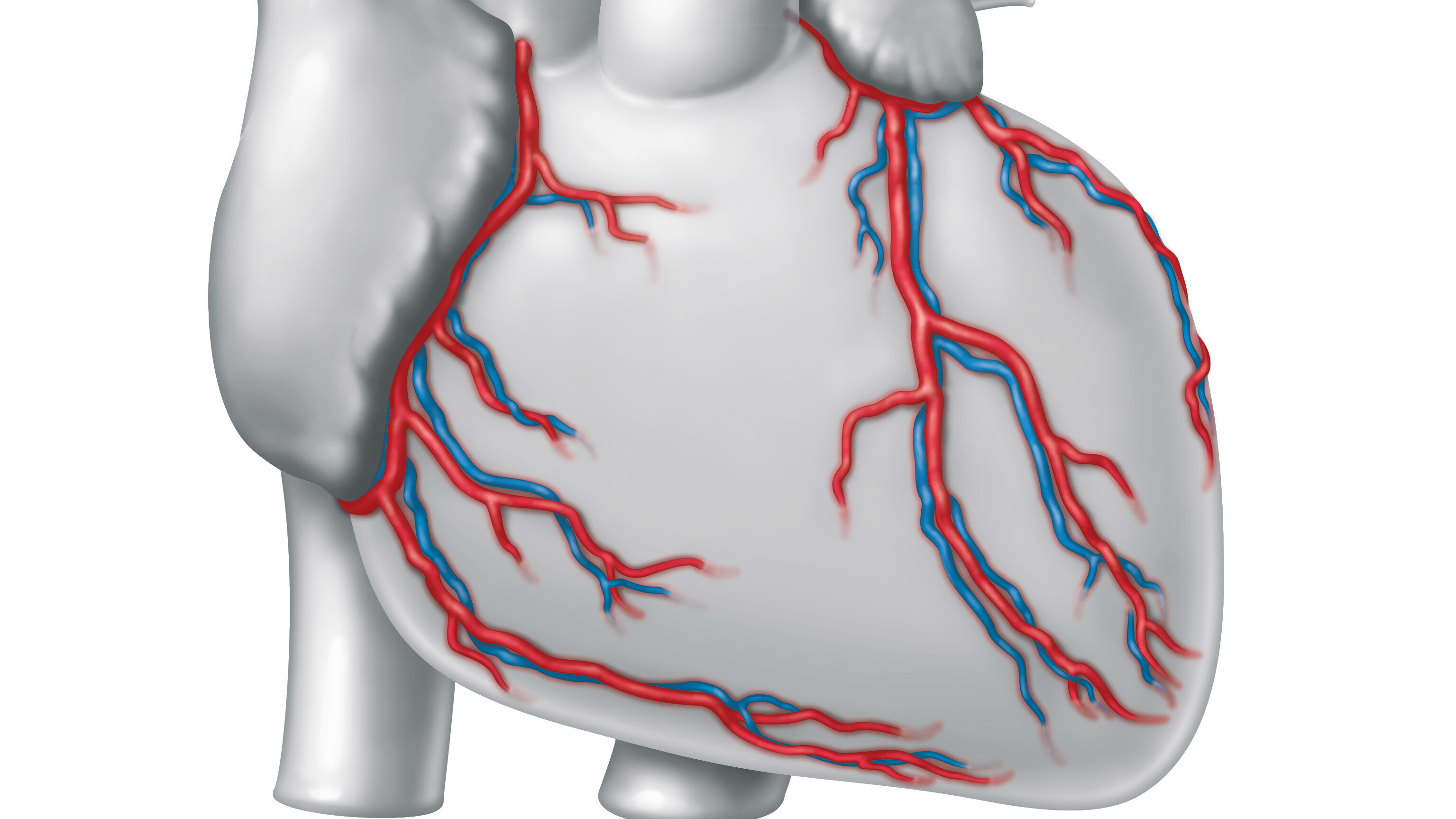

Calcified coronary arteries

Schematic representation of coronary heart disease (CHD)

Cause

Coronary heart disease is often the result of arteriosclerosis, commonly known as vascular calcification. Arteriosclerosis occurs when small inflammations form in the vessel wall. Cells, fats and other substances collect at these sites. These deposits are often not noticeable at first. However, if they increase over time, they obstruct the blood flow in the corresponding vessel.

Risk factors

There are various risk factors that favour the development of coronary heart disease:

- The most important risk factors include smoking, high blood pressure, an elevated cholesterol level, diabetes mellitus, lack of exercise and obesity.

- Age: The risk of arteriosclerosis - and therefore coronary heart disease - increases with age.

- Genes: In some families, circulatory disorders of the coronary arteries occur more frequently. If there is a family history of heart disease, there may also be a hereditary predisposition.

- Gender: While men have a higher risk of developing coronary heart disease from the age of 45, the risk for women only increases from the age of 55 when their hormone levels change.

Symptoms

The symptoms and progression of coronary heart disease depend largely on when the disease is diagnosed, whether risk factors are minimised and how patients respond to treatment.

If the coronary arteries are only slightly narrowed or calcified, patients often do not notice this.

If the calcification continues to increase, it is referred to as stable coronary artery disease. Patients suffer from angina pectoris (the feeling of ‘chest tightness’), sometimes also shortness of breath. In addition to a feeling of pressure and tightness in the chest, this sensation can also occur in the arm, shoulder, back, upper abdomen or jaw region.

If the coronary arteries close suddenly, the disease can be life-threatening. The feeling of pressure and tightness suddenly intensifies noticeably. It often occurs together with vegetative symptoms such as sweating, nausea or vomiting. In this case, there is a high probability of an acute heart attack, which must be treated immediately in a clinic.

Diagnosis

The first visit to the doctor's surgery involves taking a medical history: during the consultation, the doctor will ask about possible symptoms of coronary heart disease and a family history.

This is followed by a physical examination: the doctor measures your blood pressure, listens to your heart and determines your body mass index. The blood may also be analysed to detect metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus.

Depending on the severity of the illness, various examination methods will be carried out:

- Laboratory tests: Laboratory chemistry tests provide important information on fat and sugar metabolism. The determination of cardiac enzymes plays a particularly important role if acute coronary syndrome or cardiac insufficiency may be present.

- Resting ECG: An electrocardiogram (ECG) records the electrical activity of the heart muscle. This makes it possible to determine whether the chest pain experienced is due to an acute heart attack, whether signs of a previous heart attack are recognisable or whether cardiac arrhythmia is present.

- Ergometry/exercise ECG: The ECG is recorded under physical stress (‘cycling’). Any symptoms (angina pectoris) or changes in the ECG indicate stable CHD.

- Echocardiography: Normal echocardiography, i.e. an ultrasound examination of the heart, provides doctors with information about heart attacks that may have already gone unnoticed if coronary heart disease is suspected. In addition, a stress echocardiography can be performed, i.e. an ultrasound examination of the heart under physical stress. This examination also provides information on circulatory disorders of the coronary arteries.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): The MRI examination of the heart under artificially induced stress (‘stress MRI’) is currently the most accurate non-invasive way of diagnosing coronary heart disease. Patients are given a drug that simulates physical stress. A contrast agent is also administered.

- Computed tomography (CT): Depending on the pre-estimated probability of disease, an examination using computed tomography (CT) can also be carried out to detect coronary calcifications. This non-invasive procedure allows coronary heart disease to be ruled out with a high degree of accuracy using X-rays and contrast medium.

- Cardiac catheterisation: If the suspicion of coronary heart disease is confirmed with the help of the above diagnostics, a cardiac catheterisation is necessary. Using a thin plastic tube (catheter) and a contrast agent, the doctor can visualise the coronary arteries and the heart chambers on an X-ray screen in order to see constrictions in the coronary arteries or disturbances in the pumping force.

During a cardiac catheterisation, doctors examine the coronary vessels and the heart chambers on an X-ray screen to see whether there are any constrictions or whether the heart's pumping power is impaired

(Image: DHZC).

Therapy

Consistent drug therapy for existing risk factors as well as preventative measures in terms of a healthy lifestyle and abstaining from nicotine are the first essential pillar of therapy. It is particularly important, for example, to consistently treat existing high blood pressure, diabetes or lipometabolic disorders with suitable medication and a healthy, balanced diet.

Constrictions of the coronary arteries must be treated ‘invasively’, i.e. an intervention in the patient's body is necessary. In order to confirm the diagnosis of coronary artery disease and plan further treatment, we first carry out a cardiac catheterisation.

During the cardiac catheterisation, constrictions are widened (‘dilated’) with the help of a balloon or treated with a so-called coronary stent. This is a small tubular vascular support made of metal that is coated with a drug and stabilises the coronary vessel in the area of the narrowing.

Our experts from cardiac surgery and cardiology decide together whether a patient should be treated interventional, i.e. by cardiac catheterisation, or surgically by bypass surgery, taking current treatment guidelines into account. In addition to the patient's wishes, the decision is also based on the results of the latest studies.

The aim of this customised therapy is to treat and alleviate the symptoms - especially the chest tightness caused by exertion, ‘angina pectoris’ - in order to noticeably improve the patient's quality of life. If the heart muscle is supplied with more blood again as a result of the therapy, the risk of suffering potentially fatal secondary diseases such as a heart attack is also reduced in many patients.

In a bypass operation, constrictions are bridged with the body's own vessels (‘bypass’ in English).

In our clinic, chest wall arteries behind the constriction are usually connected to the affected coronary vessel. In addition, narrowing of the coronary arteries can be bridged by a vein from the leg or an artery from the forearm. The body can easily compensate for the loss of these vessels at the donor site. At the DHZC, doctors usually harvest the artery from the forearm endoscopically, i.e. through a small incision in the wrist. This reduces pain and the risk of wound healing disorders and leaves only a small scar.

Many bypass operations can be performed on a beating heart. The use of a heart-lung machine is not necessary, which usually contributes to a faster recovery and shorter hospital stays.

Bypass operations can also be performed minimally invasively in certain patients. The procedure is performed via a small incision below the left nipple, leaving the sternum intact.

Outpatient clinics

In our specialist cardiology outpatient clinics, we offer patients and their families comprehensive advice and treatment in close cooperation with the referring doctors and rehabilitation facilities.

Accessibility:

Mon to Fri from 07:30 to 16:00 (by appointment)

Telephone 030 4593-2420/2421

Information for referring physicians and colleagues

The ESC guidelines for chronic coronary heart disease. In our video, Prof. Dr Ulf Landmesser summarises the guidelines.