Cause

The left ventricle was unable to develop properly. This is caused by underdevelopment (hypoplasia) or complete absence (aplasia) of the ventricle.

This is usually caused by severe narrowing or complete closure of the mitral valve (mitral stenosis or atresia). Blood normally flows through this valve into the left ventricle.

Narrowing or closure of the aortic valve (aortic stenosis or atresia) can also prevent the left ventricle from developing. This valve is responsible for pumping blood from the left ventricle into the systemic circulation.

Furthermore, there is often underdevelopment of theascending artery (aorta) and the aortic arch, but in most cases the ventricular septum is intact.& nbsp;

Today, the term HLHS is also used for other forms of undersized left ventricle, namely when the left ventricle cannot support the systemic circulation and the right ventricle has to take over this task. The right ventricle now pumps blood into the lungs via the pulmonary artery, but also into the systemic circulation via a short-circuit connection (the ductus arteriosus). The problem is that the ductus normally closes after birth, which means that in HLHS, the body is practically no longer supplied with blood. Therefore, the newborn must be treated immediately after birth with medication that keeps the ductus open. This is usually possible, as the diagnosis can be made prenatally during detailed diagnostics in the second trimester of pregnancy.

Even before birth, once a diagnosis has been made, we offer detailed counseling for expectant parents about the therapeutic options available. Please contact our office to make an appointment by phone or email:

Daniela Peters, Sylvia Evers, and Mandy Müller

+49 30 2493 3400

kinderherzchirurgie@dhzc-charite.de

After delivery, the child should ideally be cared for immediately by a neonatologist, and the diagnosis of HLHS should be confirmed by a pediatric cardiologist using echocardiography. After the newborn has been treated, they should be transferred to a designated center for surgical care within the first few days of life (the DHZC pediatric cardiac emergency hotline can be reached by phone at +49 30 4593 2836; pediatric cardiology intensive care unit).

Therapy

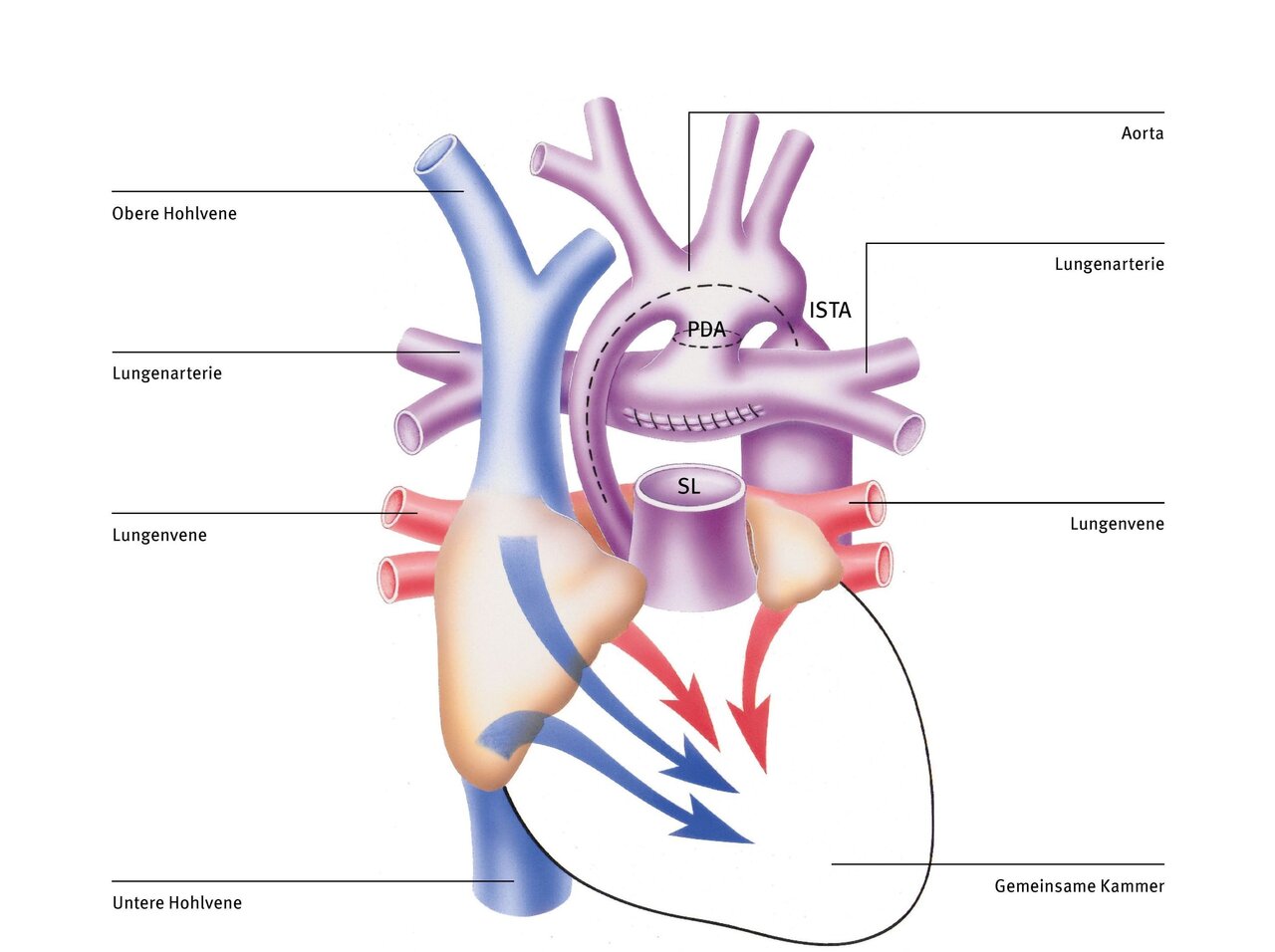

Norwood-Operation

The Norwood procedure is performed in the first days of life as a life-saving initial measure. It is the first of three operations aimed at restructuring the blood circulation so that the right ventricle, as the only pumping chamber (since the left ventricle is missing), pumps all the blood to both the lungs and the rest of the body—a difficult task.

After connecting the patient to the heart-lung machine, the pulmonary artery (PA) is first separated from the heart. Then the short circuit connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta (persistent ductus arteriosus, PDA) is severed (dashed line). Now the much too small ascending aorta and the entire aortic arch are cut open above the narrowing (aortic isthmus stenosis, ISTA) (dashed line).

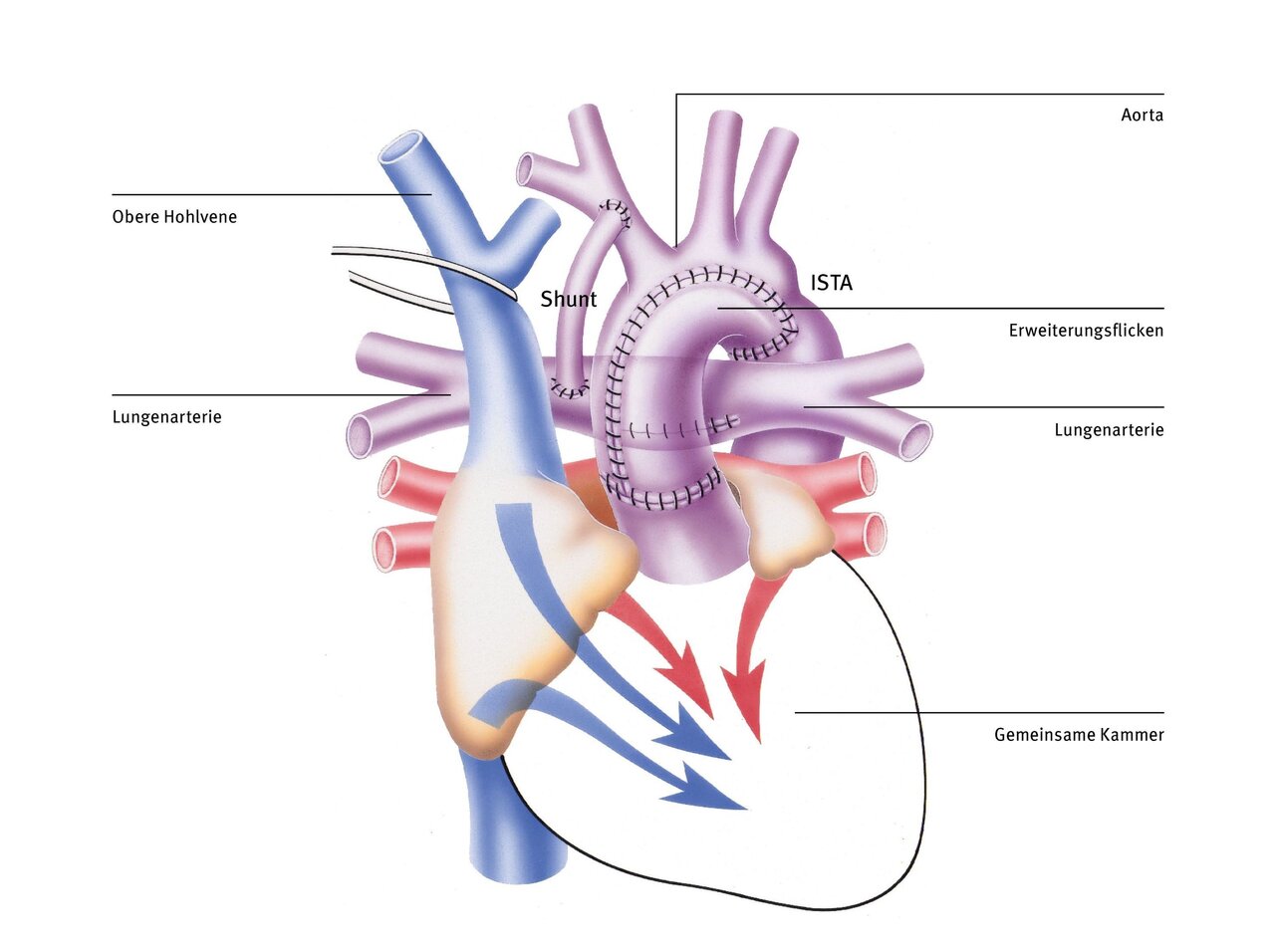

To ensure that the systemic circulation is adequately supplied with blood, the incised section of the aorta is enlarged with a patch and connected to the pulmonary artery trunk and the aortic root, which have been sutured together beforehand (Dames Kaye Stansel Anastomosis, DKS). This sufficiently widens the initial part of the aorta and the narrowing behind the aortic arch (ISTA). The right ventricle can now pump blood into the body without resistance. In addition, a small plastic tube (shunt) is sutured between a larger branch of the aorta and the pulmonary artery to direct sufficient, but not too much, blood to the lungs. Alternatively, the lungs can also be supplied by a tube that is connected directly to the right ventricle (Sano shunt variant).

After the Norwood procedure, the mixed blood flows unimpeded into the right ventricle and from there also unimpeded into the aorta, as the narrow section at the beginning and the narrowing behind the aortic arch have now been widened with a patch. The blood supply to the lungs is ensured by means of the plastic tube between the aorta (or the right ventricle) and the pulmonary artery.

After recovery from the Norwood procedure, further operations follow at the age of four to six months (Glenn procedure) and at the age of two to three years (Fontan procedure), in which the pulmonary and systemic circulation are gradually separated, thereby significantly reducing the strain on the right ventricle.

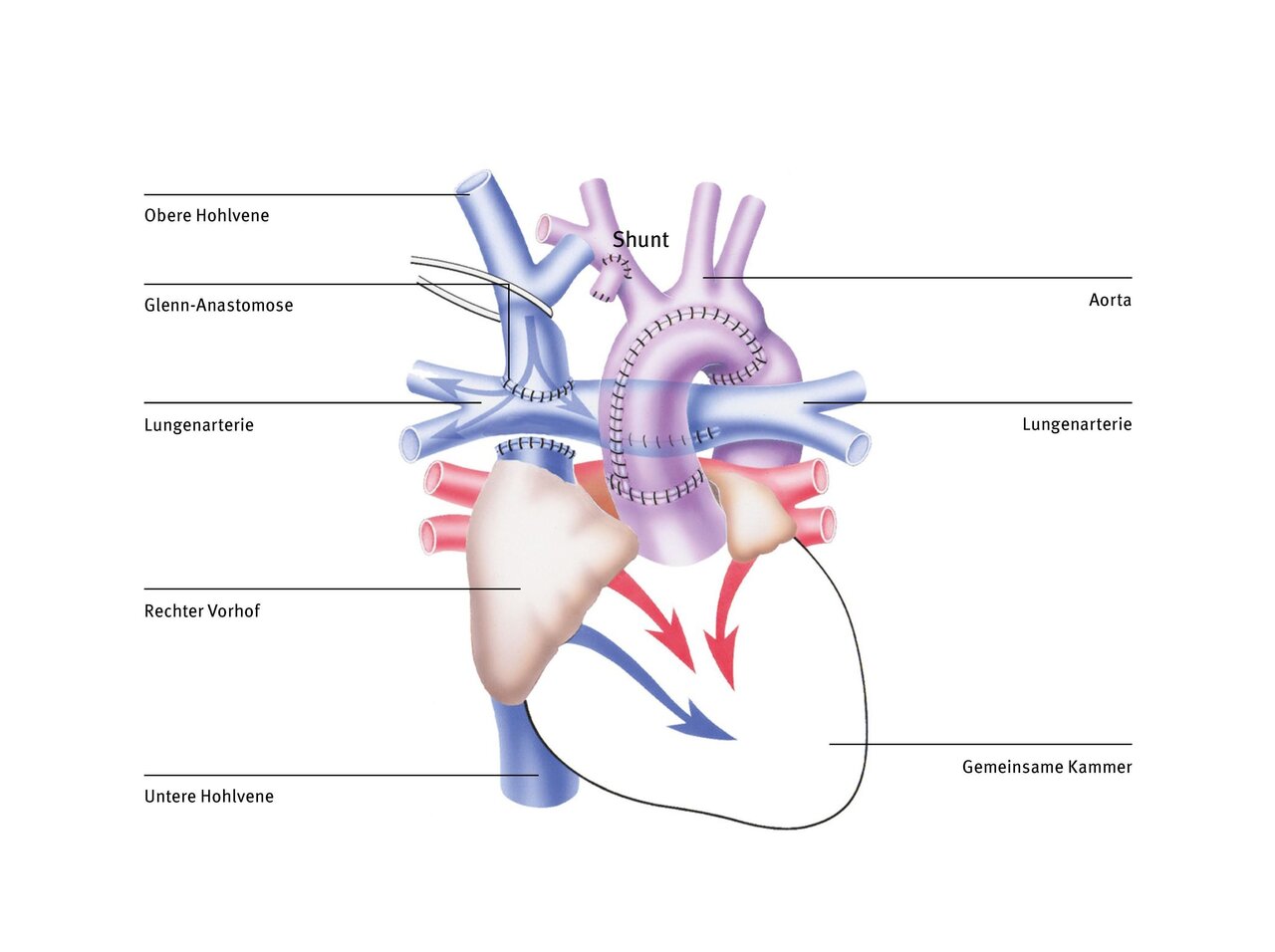

Bidirectional Glenn procedure (superior cavopulmonary anastomosis)

The right ventricle, which normally only pumps blood into the pulmonary circulation, supplies the entire body with blood after the Norwood procedure. This ventricle would certainly be overwhelmed if this were to continue for a longer period of time, as it normally only supplies the pulmonary circulation and not the systemic circulation (this task is performed by the left ventricle in a normal heart). Another disadvantage is that only mixed blood flows in both circulatory systems.

With the bidirectional Glenn procedure (also known as superior cavopulmonary anastomosis), the systemic and pulmonary circulatory systems are partially separated. The plastic tube is removed and the superior vena cava is separated at the level of the right atrium and connected directly to the right pulmonary artery. The operation partially relieves the right ventricle, which previously had an increased workload. However, this anastomosis can only be performed after vascular resistance in the pulmonary vessels has decreased at the age of three to six months. The blood can then flow passively through the lungs, driven only by gravity and the suction created when inhaling.

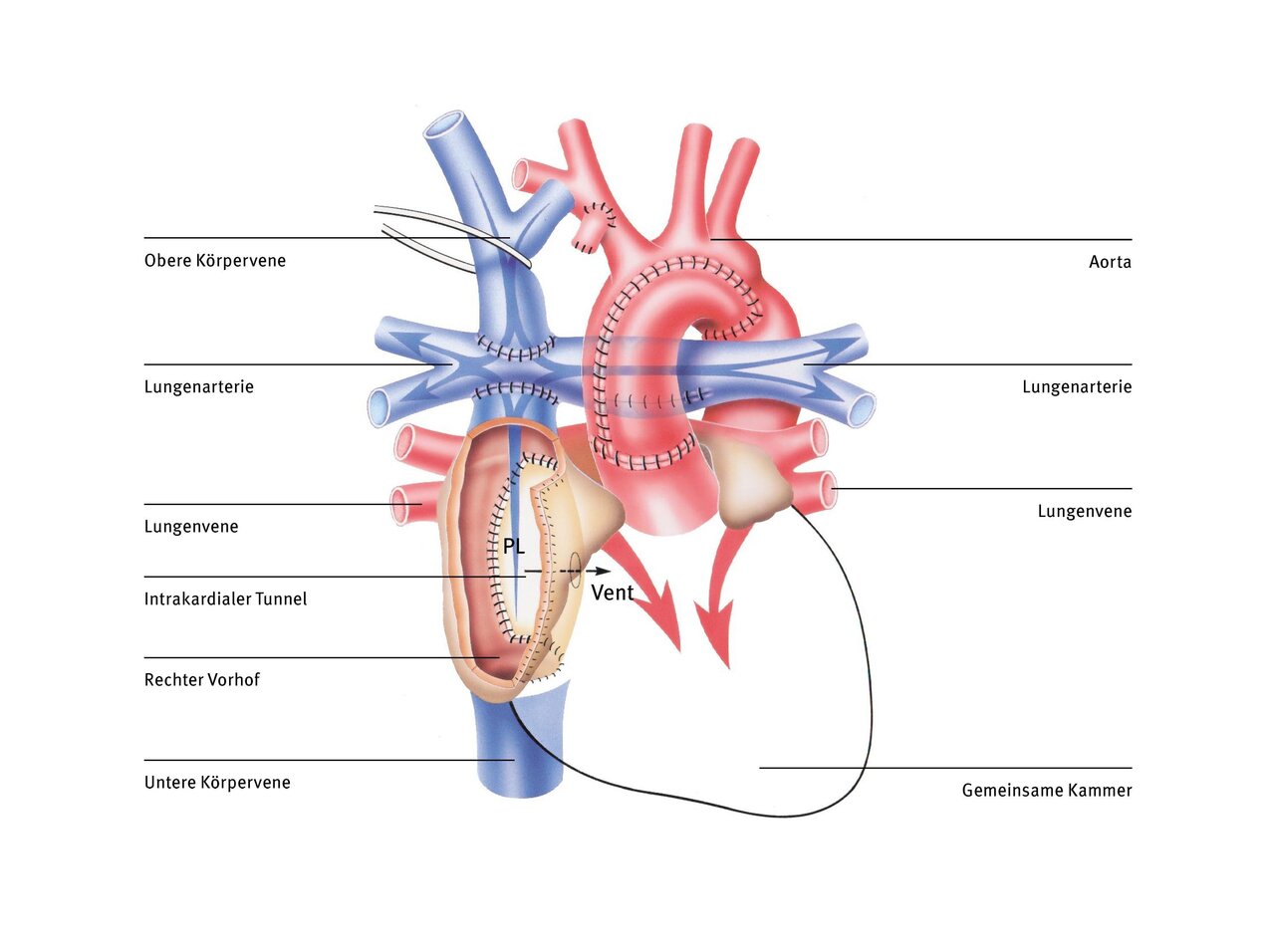

Fontan operation (Norwood stage 3)

The Glenn operation ensures that the deoxygenated blood from the superior vena cava flows directly into the lungs and no longer mixes with the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs in the common ventricle. However, the blood from the inferior vena cava has not yet been diverted because the pulmonary vessels were not yet ‘big enough’ to absorb all the blood from the systemic circulation. In order to better relieve the single ventricle, the blood from the inferior vena cava must also be channelled directly into the lungs instead of into the common ventricle.

There are various techniques for this. The most commonly used today is total cavopulmonary anastomosis (TCPC), in which a tube (tunnel) is led past the outside of the heart and connects the vein to the pulmonary artery. This type of venous blood supply to the lungs was first developed by the Frenchman Francis Fontan in the 1980s and the circulation that is achieved with it is also known as the Fontan circulation. During the Fontan operation, the inferior vena cava is connected to the pulmonary artery in the form of a Goretex tunnel outside the heart. The pulmonary and systemic circulation are thus completely separated from each other.

Therapy at the German Heart Center at Charité

Over the past ten years, the German Heart Center at Charité has become a leading center for the treatment of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. The survival rate for Norwood surgery is currently over 90%, which is an outstanding result by international standards. Various treatment and surgical techniques have been continuously adapted and improved.

If the patient is hemodynamically stable and free of infection, we perform the Norwood procedure within the first four days of life. Early surgery is intended to prevent the possible development of preoperative complications and is associated with a better postoperative outcome after Norwood palliation (Anderson BR et al., 2015).

Today, we no longer perform the operation under circulatory arrest with the patient cooled to below 18°C, but with a temperature reduction to only 28°C and continuous blood flow to the upper and lower half of the body via special cannulas in the arteries of the head and leg vessels. The method is relatively simple, quick, and low in complications, and allows continuous blood flow to the brain and abdominal organs during the aortic arch reconstruction phase (Boburg et al.).

We have also changed our shunt preferences: from the modified Blalock Thomas Taussig variant (BTT, with a plastic shunt from the right carotid artery and brachial artery to the right pulmonary artery) to the now more commonly used Sano shunt (from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery). In a large comparative study, this variant has been shown to offer not only the already known more stable circulatory status but also a survival advantage up to the age of five (Newburger et al. 2014). After that, the survival curves for BTT and Sano shunts become similar.

However, pure survival is only one treatment outcome; improved physical and mental development is another significant one. Since we see a much more stable circulatory position and a shorter and less complicated postoperative course in the first four to six months until the Glenn operation with the Sano shunt variant, better development can also be expected. This is confirmed by a study on intellectual development in relation to the circulatory stability of infants (Newburger et al. 2012).

The BTT shunt variant is currently only used in special circumstances, e.g., tricuspid valve atresia with transposition and hypoplastic aortic arch, because there is hardly any space for attaching the Sano shunt to the outlet chamber, which is too small, or because a reliable blood supply from the outlet chamber cannot be expected.

Home monitoring with the EVIE app reduces the mortality rate between the first Norwood operation and the subsequent Glenn operation (interstage) to almost zero. All children receive a monitor that allows parents to record oxygen saturation, body weight, heart rate, and temperature after measurement and transmit the data to the DHZC using the Evie smartphone app. The data is transmitted daily and immediately, and parents are contacted immediately if any abnormalities are detected. If necessary, the infants are admitted to the hospital promptly.

Video: A mother tells her story

Salih was born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and was successfully treated at the DHZC. In our video, his mother Gülcan I. speaks openly about how she experienced the period from diagnosis to the third operation.

References

- Anderson BR et al. Eine frühzeitige Palliation im Stadium 1 ist mit besseren klinischen Ergebnissen und geringeren Kosten für Neugeborene mit hypoplastischem Linksherzsyndrom verbunden. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149(1):205-10.e1.

- Boburg et al. Selektive Perfusion des Unterkörpers während einer Aortenbogenoperation bei Neugeborenen und Kleinkindern. Perfusion 2020;35:621–5.

- Newburger et al. Circulation. 2014;129:2013-2020 Newburger et al. Circulation. 1. Mai 2012; 125(17): 2081–2091.

- Rosenthal et al. Anwendungsbasierte Fernüberwachung für Säuglinge mit shunt- oder duct-abhängiger Lungenperfusion zu Hause. Front Cardiovasc Med 2025;11:1493698.