Atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD)

The atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) is a congenital defect characterised by a gap in the wall between the heart cavities. This gap allows blood to flow between the two atria and the two ventricles.

AVSDs are categorised into different sizes and degrees of severity, from small defects that cause few symptoms to severe defects that can lead to serious complications such as heart failure, pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary hypertension. An AVSD usually requires surgical intervention to close the defect and avoid complications.

Symptoms

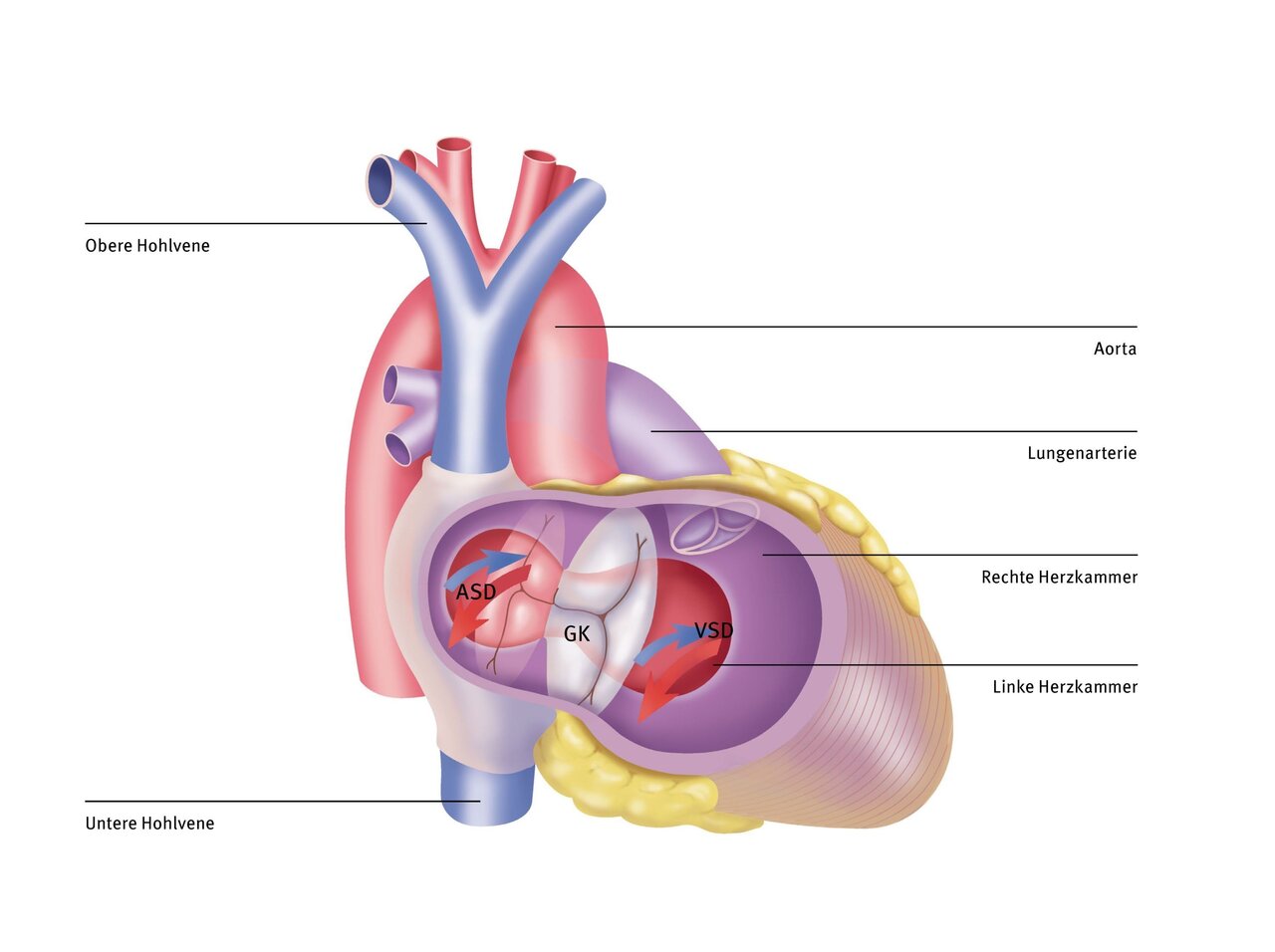

The deoxygenated blood travels via the superior and inferior vena cava into the right atrium and from there into the right ventricle. In the atrium, the deoxygenated blood from the systemic circulation mixes with the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs, which crosses the atrial septal defect (ASD). The same happens in the ventricles. Oxygen-rich blood passes through the ventricular septal defect (VSD) from the left to the right ventricle or directly into the pulmonary artery. Due to these large defects in the atrial and ventricular septum, the two heart valves that separate the left and right atrium from the left and right ventricle (mitral and tricuspid valves) have no support on the ventricular septum. Instead, they are fused to form a common valve (GK).

All four heart chambers are connected to each other via the two defects. The left ventricle, in which the pressure is higher than in the right ventricle, pumps blood into the pulmonary vessels in addition to the right ventricle, which can be damaged as a result. This additional flow first reaches the left atrium from the pulmonary vessels. From there, it is partly channelled into the right atrium and then back into the left ventricle. Both are unnecessarily overloaded as a result. To correct this heart defect, both the ASD and the VSD must be closed and the common valve turned into two valves.

Symptoms

Normally, the right side of the heart, i.e., the right atrium and right ventricle, pumps blood into the pulmonary circulation, and the left side of the heart, i.e., the left atrium and left ventricle, pumps blood into the systemic circulation. If AVSD is present, blood flows from the left heart to the right heart, placing additional strain on the right heart and lungs. This blood flow can cause permanent damage to the right heart and pulmonary arteries.

In some children, the leaky valve between the atria and ventricles can cause blood to flow back from the ventricles into the atria. This backflow, also known as heart failure, puts additional strain on the heart.

Children with AVSD may exhibit rapid and labored breathing and cold sweats with little exertion. Problems with breastfeeding or feeding and resulting slow growth are also common and reflect the extra work the heart has to do due to the defect.

If AVSD remains untreated for a long period of time, excessive blood flow to the pulmonary arteries leads to high blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries (“pulmonary arterial hypertension” or PAH). PAH is difficult to treat and is associated with a significantly reduced life expectancy.

Diagnosis

The methods most frequently used at the DHZC are

- Electrocardiography

- Echocardiography

- Cardiac catheterisation if necessary

- Computed tomography if necessary

- Magnetic resonance imaging if necessary

- Chromosome analysis if necessary (45 per cent of all patients with Down syndrome have an AVSD)

What is echocardiography?

The difference between ultrasound and echocardiography is that ultrasound is a more generalised form of imaging that is also used in other areas such as obstetrics and for other organ systems. Echocardiography, on the other hand, is a specialised form of ultrasound examination. It was developed specifically for the examination of the heart. Echocardiography is a non-invasive method that can be used for diagnosis and follow-up, while cardiac catheterisation is an invasive method that is used, for example, for detailed examination of the heart and blood flow.

An atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) can be detected very reliably using echocardiography (heart ultrasound)—this is the main method used for diagnosis. This involves viewing the heart from different angles in order to assess the anatomy and function of the heart walls and valves.

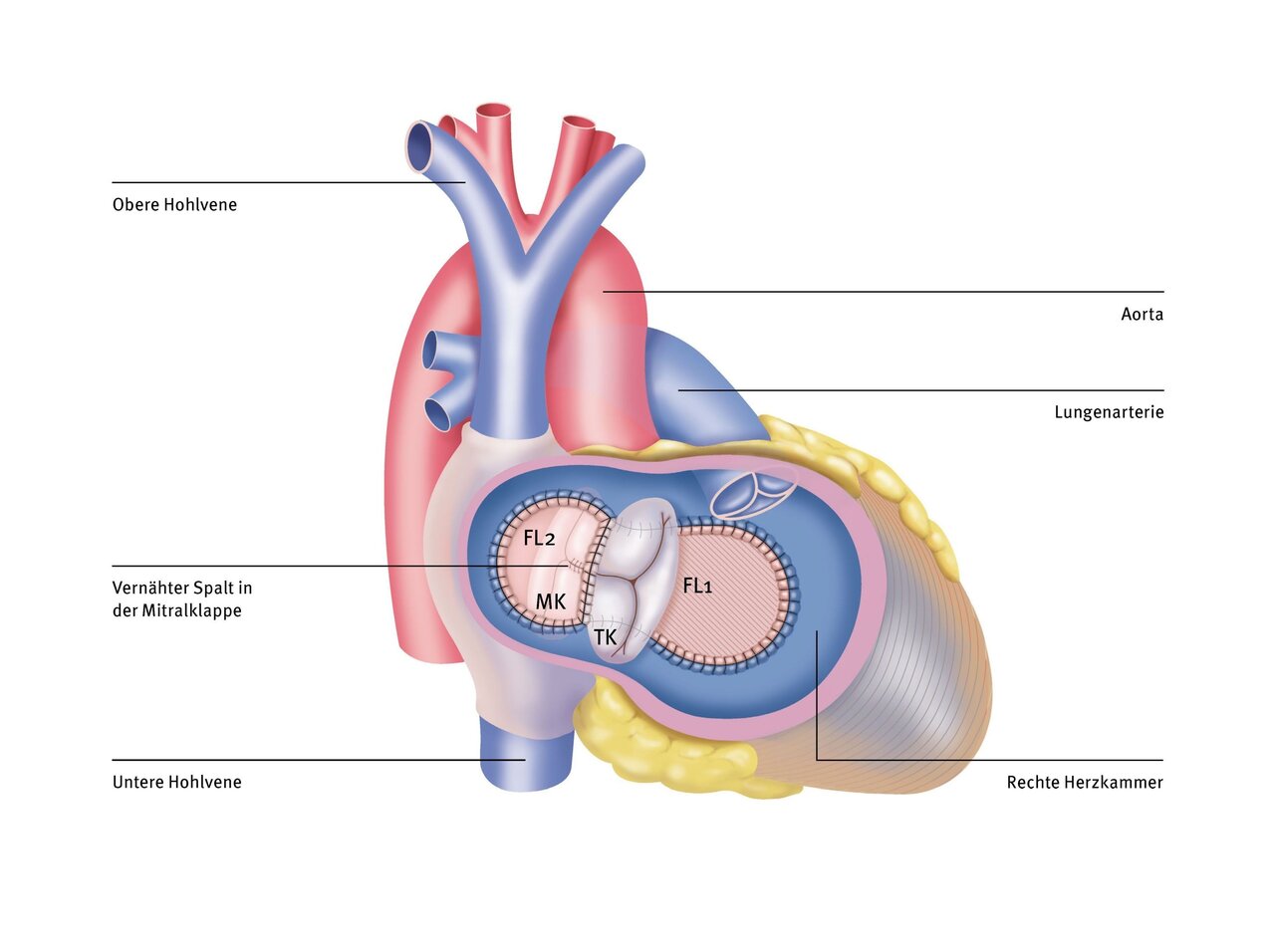

Operation at the DHZC

After connecting the heart-lung machine (HLM), the large defect in the septum can be seen through an incision in the right atrium. Firstly, a plastic patch is sewn between the two heart chambers (closure of the VSD). The common valve is cut so that it can be divided: one for the left ventricle (mitral valve = MK) and one for the right ventricle (tricuspid valve = TK). The two edges of the new valves are sewn to the upper edge of the patch. A second patch is then sewn between the two atria (closure of the ASD) and the heart is then closed again.

The deoxygenated blood, which collects in the right atrium via the superior and inferior vena cava, flows through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. From there it is pumped into the pulmonary artery. The first patch separates the left and right ventricles and prevents oxygen-rich blood from being pumped from the left ventricle into the pulmonary vessels. The oxygen-rich blood from the lungs flows into the left atrium and via the mitral valve (MK) into the left ventricle. The second patch prevents oxygen-rich blood from flowing from the left atrium into the right atrium. As usual, the left ventricle pumps the blood into the aorta (body artery). A gap in the mitral valve should be closed if possible to prevent the valve from leaking later.

Questions and answers for parents (FAQ)

After successful AVSD correction, your child can usually engage in normal physical activity. Immediately after AVSD correction, it may be necessary to refrain from strenuous activity for a short period of time until healing is complete. Some children may need to avoid more strenuous activity. Your pediatric cardiologist will advise you individually on this.

Even after successful correction of an AVSD, you should have your child undergo regular follow-up examinations with your pediatric cardiologist. In particular, the valves between the atria and ventricles may become leaky again or develop narrowings over time. This may necessitate further surgery and, if necessary, a change in medication.

For a period of about six months after AVSD correction, your child will need to take antibiotics as a preventive measure before certain procedures, such as dental work. This procedure is called “endocarditis prophylaxis” and is intended to prevent bacteria that enter the bloodstream during dental work from settling in the previously operated heart. Your pediatric cardiologist will discuss with you individually whether this endocarditis prophylaxis needs to be continued for more than six months.

The outlook for life expectancy and quality of life is good after timely AVSD correction. However, since AVSD is a complex heart defect, heart problems can still occur in the years following an initially successful correction in infancy. These often affect the heart valves, which can become leaky or too narrow again. This may necessitate further surgery and, if necessary, replacement of the valve with a prosthesis.

During the initial corrective surgery, cardiac arrhythmias may occur, requiring the implantation of a pacemaker. The function of such a pacemaker must be regularly monitored by a pediatric cardiologist. After a few years, the pacemaker must be replaced due to the inevitable depletion of the battery.

If further surgery or regular pacemaker replacement is necessary, this can have a negative impact on your child's quality of life and life expectancy.

Even if the corrective surgery is successful, leaks or narrowings may occur in the reconstructed valve over time. This may necessitate further reconstruction, i.e., repair of the valve using the body's own material, or replacement of the valve with a prosthesis.

If a cardiac arrhythmia occurred after the first operation, requiring pacemaker implantation, the pacemaker will need to be replaced several times during the patient's lifetime due to the limited battery life.