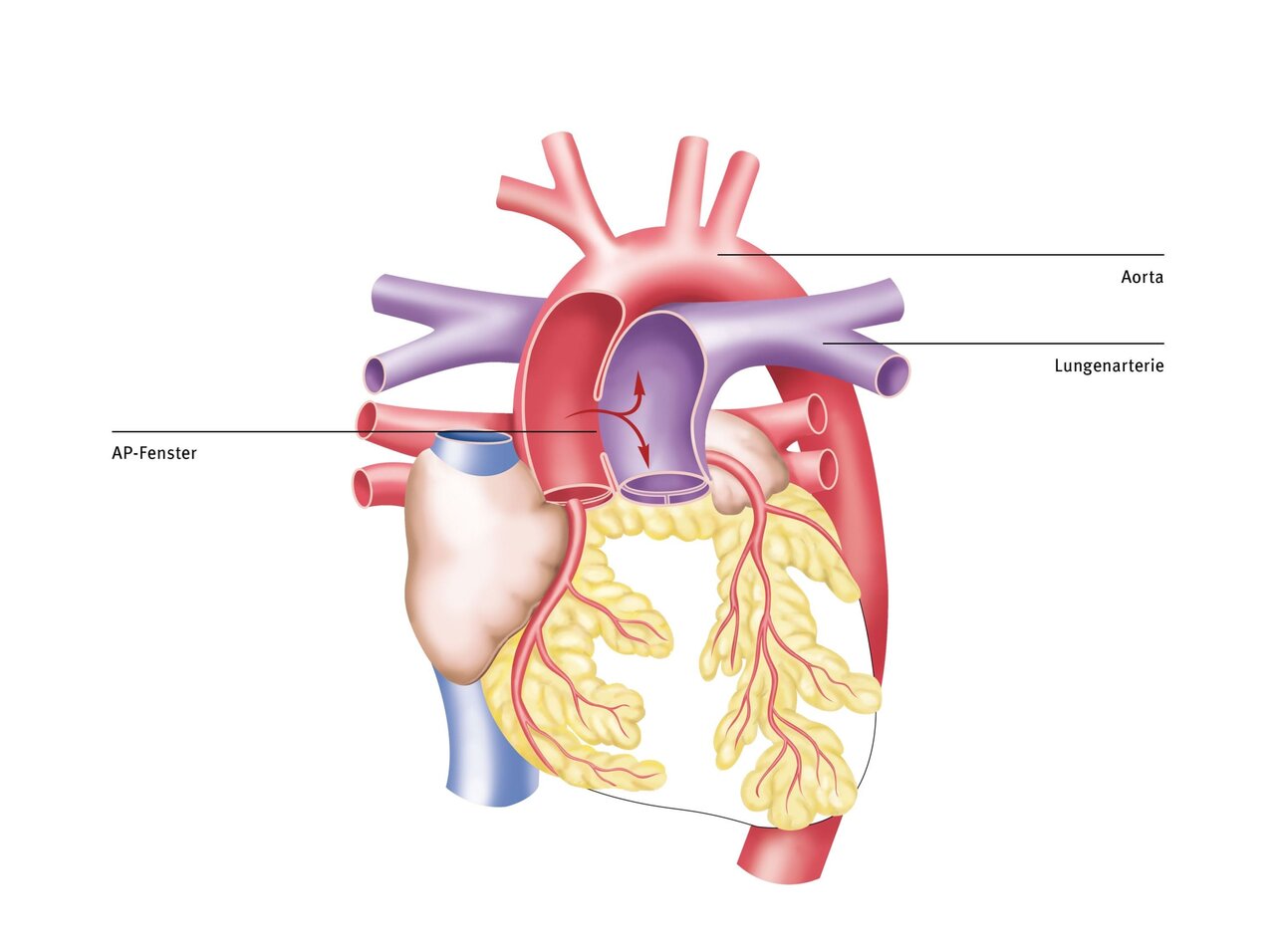

Aortopulmonary window

The aortopulmonary (AP) window is a very rare congenital heart defect in which there is an open connection between the main artery (aorta) and the pulmonary artery (pulmonary artery). Due to the high blood pressure in the aorta, too much blood is pumped into the lungs. Pulmonary hypertension develops. Signs of cardiac insufficiency, such as feeding difficulties and failure to thrive, can therefore occur as early as infancy.

Risk factors

The aortopulmonary window is caused by incomplete separation of the aorta and pulmonary artery during the first three months of pregnancy. The reasons for this malformation are unclear. However, it is believed that many different factors, genetic changes (gene defects), or environmental influences during pregnancy may play a role.

Causes and effects

Due to the higher blood pressure in the aorta, a large amount of blood flows into the lungs, a condition known as pulmonary congestion. This requires the heart to work harder, which can lead to strain and ultimately to heart failure. In addition, the pulmonary vessels change over time in order to better withstand the increased pressure. This results in pulmonary hypertension, which can lead to reduced pulmonary blood flow.

Symptoms

Depending on the size of the defect, children are usually diagnosed in the first weeks to months of life with signs of heart failure such as

- Increased respiratory rate (tachypnoea),

- drinking difficulties,

- failure to thrive and

- frequent pulmonary infection

are conspicuous. The symptoms are similar to those of a persistent ductus arteriosus (PDA) but usually occur earlier.

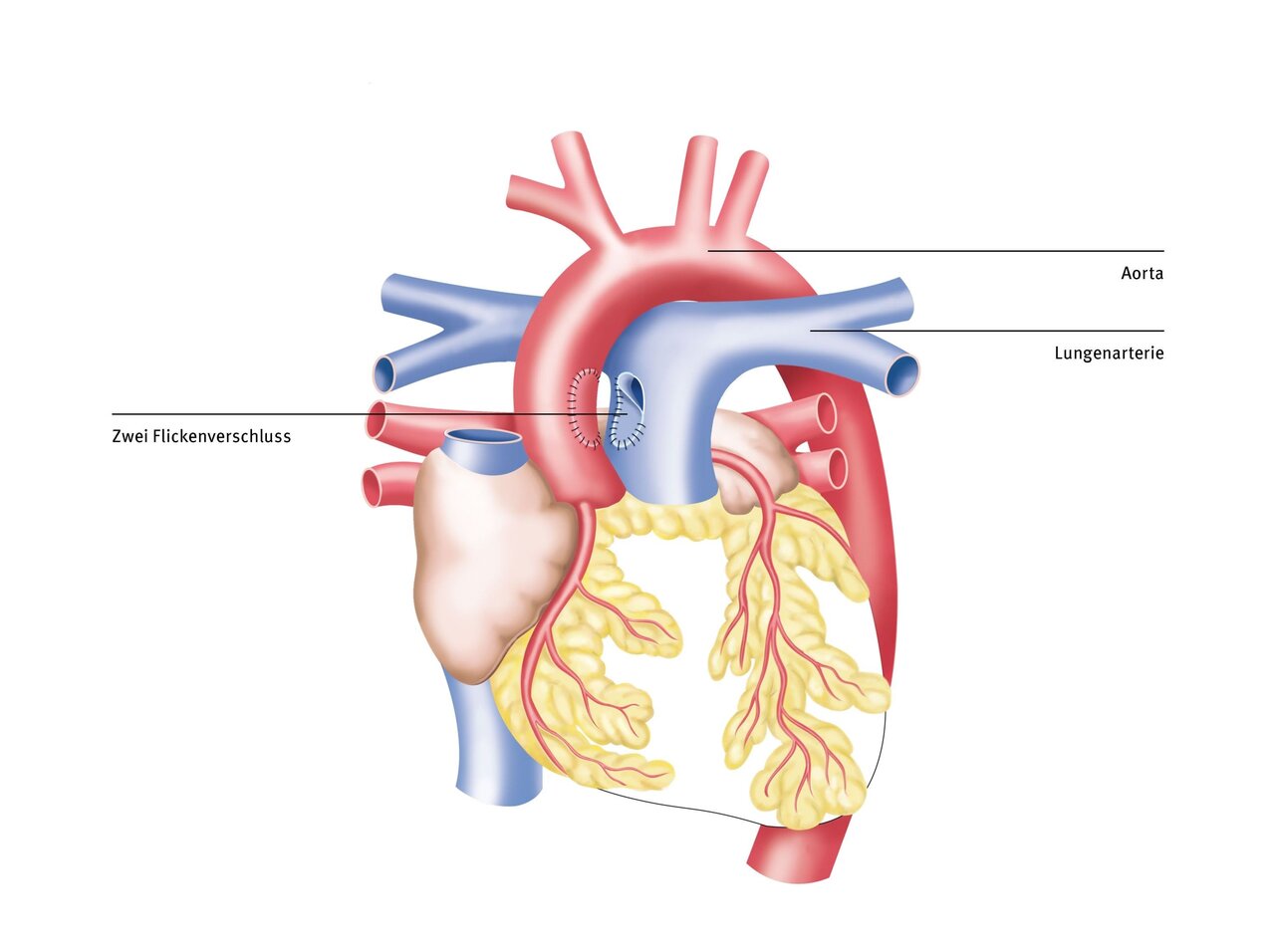

Therapy at the DHZC

Since the aortopulmonary window is a very rare congenital heart defect that must be corrected in newborns, these patients should be treated in centers with proven expertise. In addition to the surgical and technical challenges of operating on newborns, complications such as pulmonary hypertension crises can occur in the postoperative period. This leads to a sudden increase in pressure in the pulmonary vasculature, so that only a small amount of blood can flow back through the lungs and to the left heart. This results in circulatory collapse, a life-threatening complication.

At the German Heart Center at Charité (DHZC), we have extensive experience in caring for newborns after corrective surgery. Our intensive care unit is staffed by pediatricians, pediatric intensive care physicians, and pediatric intensive care nurses with years of experience. They are familiar with such complications and can therefore avoid them or detect them early and treat them in a timely manner.

In the rare event that heart failure occurs after corrective surgery that cannot be remedied with medication, we have heart support systems of all sizes available. The artificial heart treatment team at the DHZC has the most experience worldwide in the use, handling, and removal of such artificial heart systems in children and adults. Our extensive experience with such rare and complex heart defects is reflected in the excellent postoperative outcomes of our patients. Further information can be found in our externally validated quality assurance standards and our annual quality reports.

Follow-up care

If the diagnosis is made early and the aortic-pulmonary window is closed in a timely manner, the prognosis is very good. However, the heart is usually still enlarged due to the previous strain. Therefore, many infants still require medication for several weeks to months, which can be gradually reduced and eventually discontinued as planned by the pediatric cardiologist.

The sternum, which we have to cut lengthwise during this operation, usually takes about four to six weeks to heal completely and become stable. After that, normal resilience, quality of life, and life expectancy can be expected.