Ventricular septal defect (VSD)

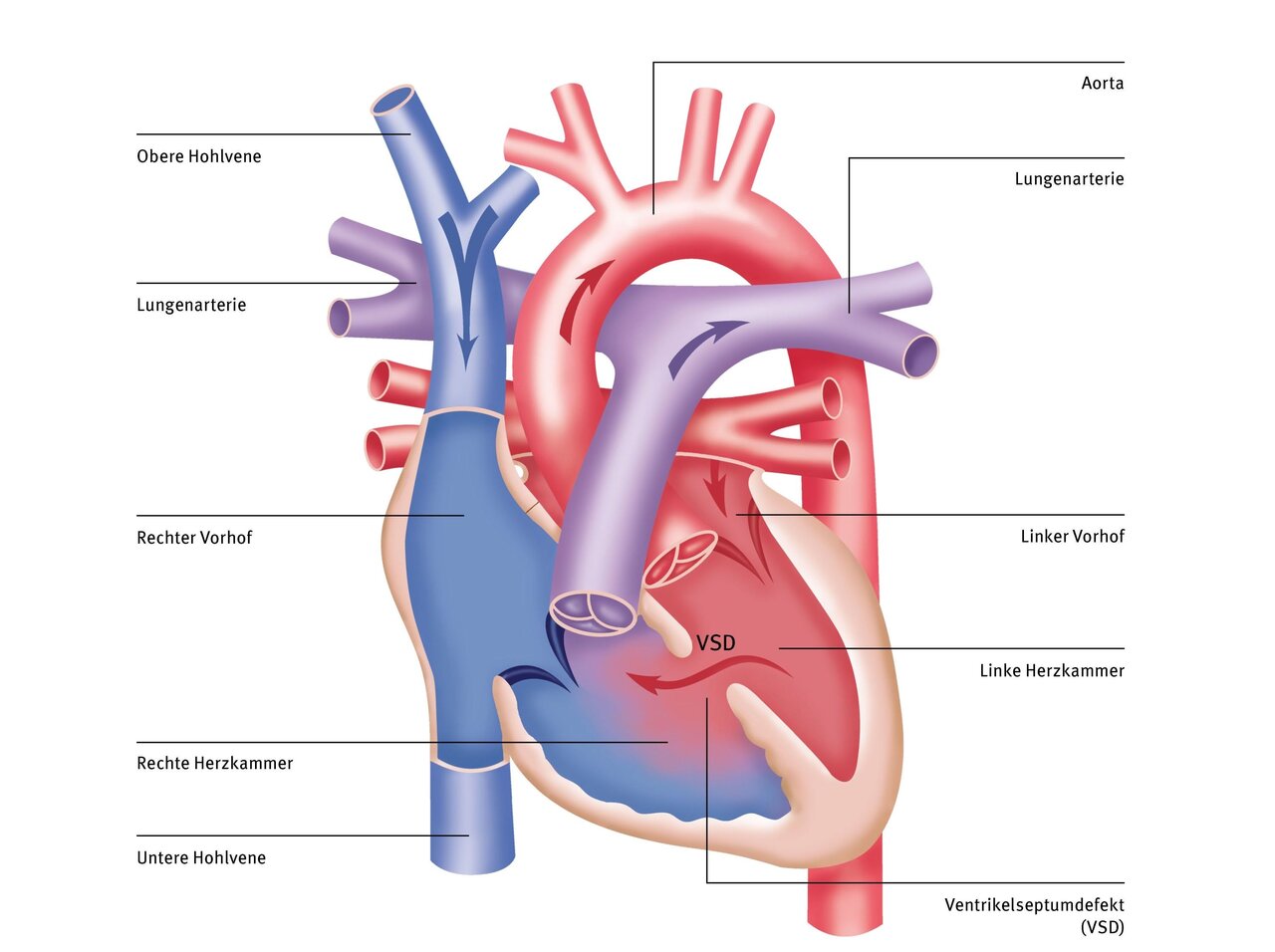

Ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a heart defect in which the septum between the ventricles is not completely closed. The so-called ‘hole in the heart’ is the most common congenital heart defect. However, a VSD can also occur as a result of a heart attack or after heart surgery.

Depending on the localisation, a distinction is made between defects in the muscular, perimembranous, outlet or inlet area of the ventricular septum. Through the connection between the two ventricles, some of the oxygen-rich blood flows from the left ventricle into the right ventricle, where it mixes with the deoxygenated blood (left-to-right shunt). This causes a larger volume of blood to enter the pulmonary circulation, which increases the pressure in the pulmonary vessels and results in pulmonary hypertension. The right ventricle is exposed to an increased pressure load due to the increase in blood pressure in the pulmonary vessels. The left ventricle has an increased volume load due to the increased amount of blood that returns to the left ventricle via the pulmonary vessels. The extent of this pressure and volume load depends on the size and number of defects present (pressure-separating or non-pressure-separating VSD).

Causes and risk factors

During development in the womb, every child initially has a defect in the heart septum. Normally, however, this defect closes long before the child is born, between the 6th and 8th week of pregnancy. Sometimes, however, the heart septum does not close completely.

The reason for this is not yet known, but many factors appear to play a role. Some children also have other heart defects in addition to VSD. In some cases, genetic syndromes such as trisomy 21 are associated with congenital heart defects.

Symptoms

The symptoms depend on the size of the VSD and the extent of the shunt volume. The most common symptoms in infants are difficulty drinking, failure to thrive, rapid and laboured breathing (tachydyspnoea) or an increased tendency to become infected. In children and adults, VSD can be characterised by increased tiredness and fatigue as well as reduced resilience (breaks during play or physical exertion). Palpitations or a bluish discolouration of the skin (cyanosis) may also occur.

Therapy at the DHZC

At the DHZC, we can perform most VSD closures using a cosmetically advantageous, minimally invasive approach on the right side of the chest. Alternatively, a smaller incision can be made in the lower part of the sternum (partial sternotomy). These incisions will not leave any stigmatizing large skin incisions.

At the DHZC, we offer the fast-track concept for operations such as VSD closures whenever possible. This means that your child will be weaned off the ventilator while still in the operating room and will be transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit already breathing independently. These procedures contribute to fewer ventilation-related complications, a shorter stay in the intensive care unit, and, overall, a faster recovery and discharge home.

In older children and if the VSD is small and in a favorable location, it can sometimes be closed using a cardiac catheter procedure with umbrella implants. To do this, a sheath is placed in an arterial vessel in the groin and the VSD is probed via the left ventricle after a catheter has been inserted.

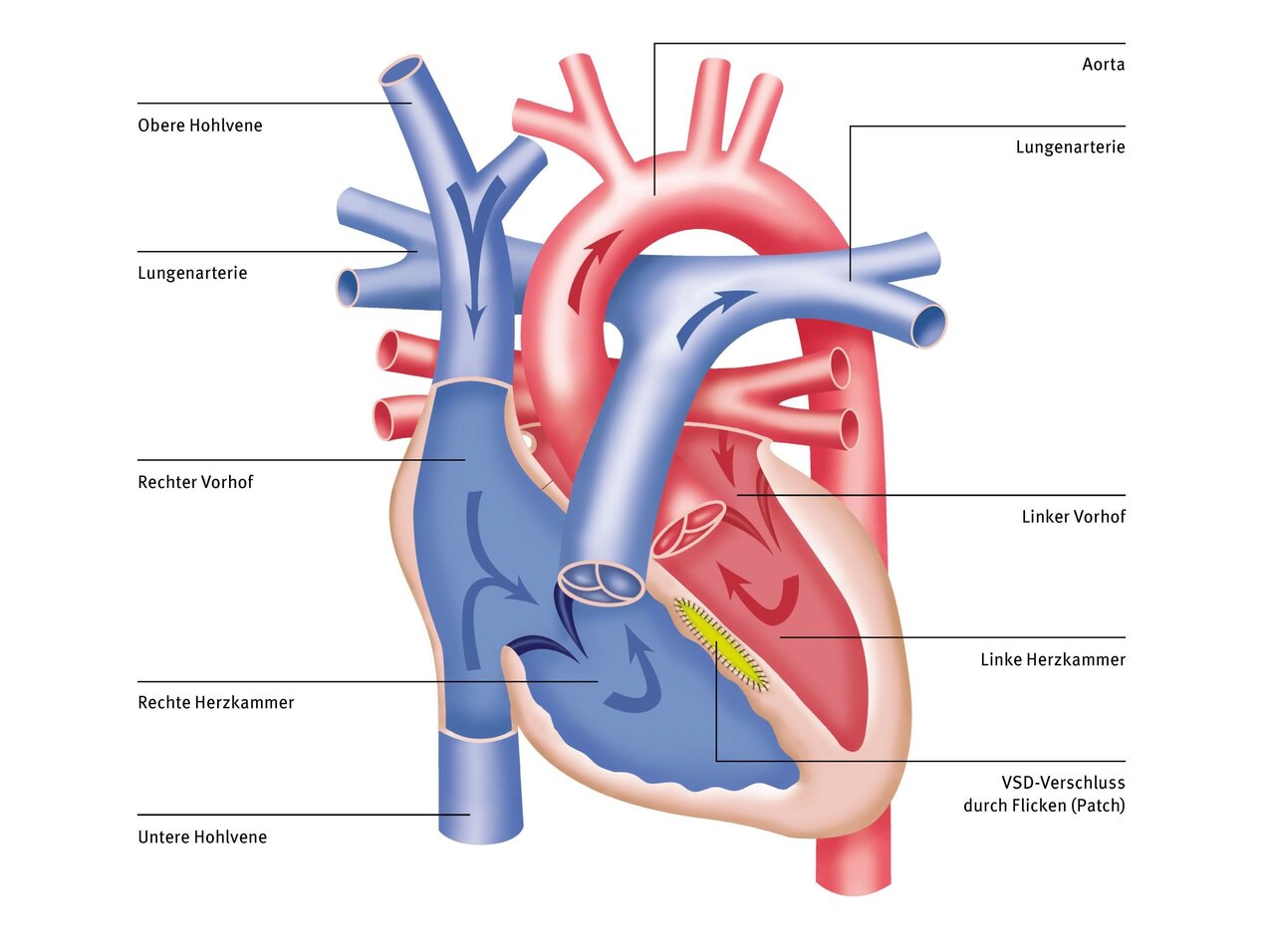

If your child is very ill, still very small, or even premature, and the VSD is large, it may not be possible to close the defect immediately. In this case, there is a surgical option that alleviates the symptoms for a limited time and protects the pulmonary vessels from high pressure. This option is called pulmonary artery banding (PAB). In this procedure, a band is placed around the pulmonary artery while the heart is beating, usually without the use of a heart-lung machine, thereby artificially narrowing it. This reduces the flooding of the lungs, protecting them. Once your child has grown a little, the band is removed during corrective surgery and the VSD is closed with a patch.

The sternum, which we have to cut lengthwise during this operation, usually takes about four to six weeks to heal completely and become stable. After that, there is nothing to prevent normal physical activity. Further information can be found in our externally validated quality assurance standards and our annual quality reports.

Possible complications in the long term

The child's prognosis for the underlying heart defect is good in the short and long term. After an adaptation phase, the patient is considered to have a healthy heart. Immediately postoperatively, residual defects (<3 mm diameter) are often detectable, which are generally no longer haemodynamically relevant.

Recommendation for follow-up treatment

We recommend continuing endocarditis prophylaxis with the known indications for six months after surgical or catheter-interventional closure of the VSD.