Subvalvular aortic stenosis / subaortic stenosis

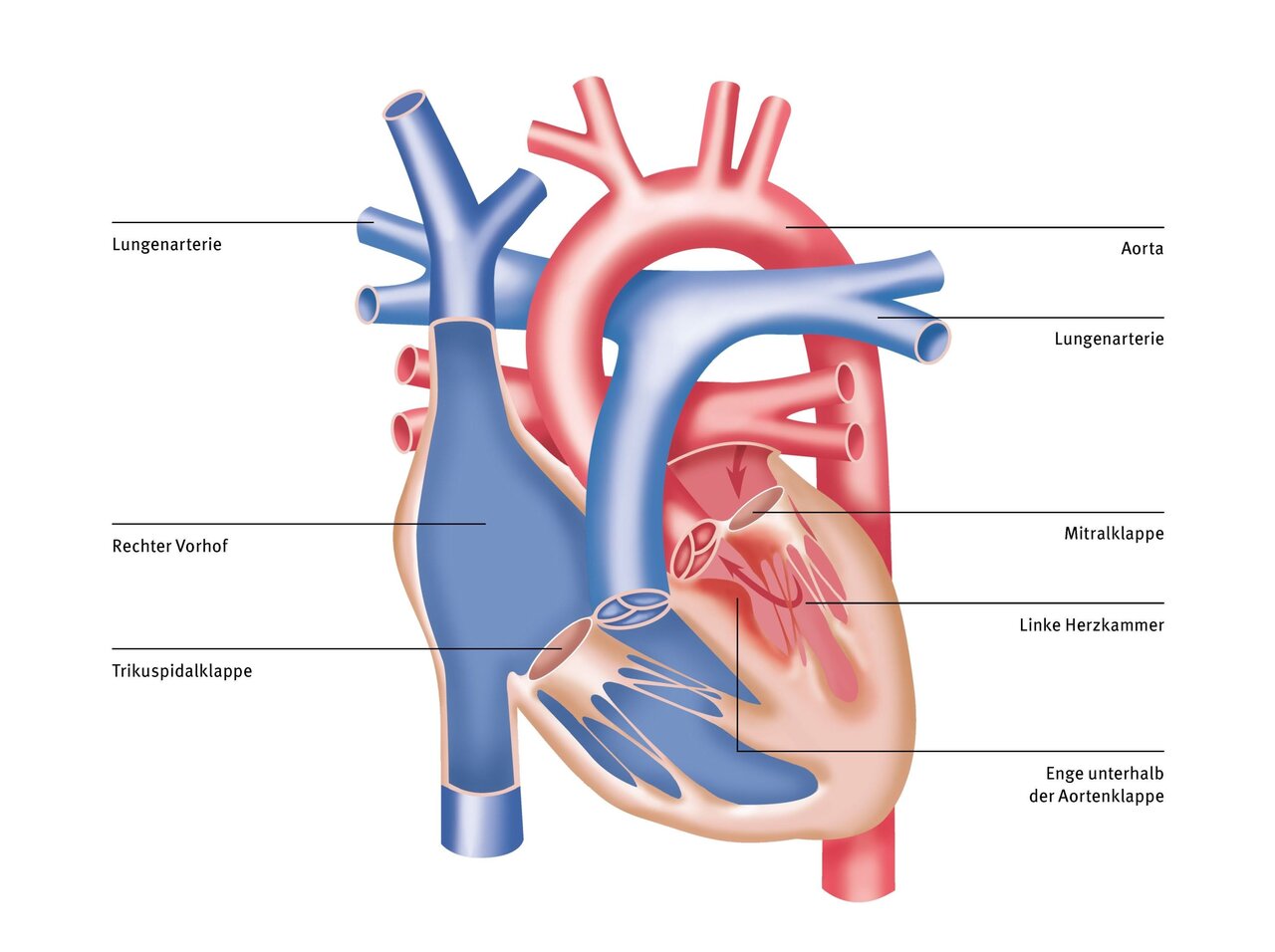

The term “subvalvular aortic stenosis” refers to a narrowing of the outflow tract of the left ventricle below the valve flap (aortic valve), which prevents blood ejected from the ventricle from flowing back into the ventricle.

The narrowing is caused by a membrane of connective tissue or by a thickened heart muscle. As a result of the turbulence of the blood flow in this area, the narrowing can increase steadily over the course of a lifetime. Subvalvular aortic stenosis can also occur in the context of complex heart defects or as a residual finding after surgical procedures.

Cause

In a normal heart, oxygen-rich blood flows from the lungs through the left atrium into the left ventricle and is pumped from there through the aorta without obstruction throughout the body. In this situation, the heart can easily overcome the resistance offered by the body's blood vessels. The wall thickness of the heart muscle and the coronary vessels necessary for supplying oxygen to the heart muscle remain in a clearly defined balance.

If there is narrowing below the aortic valve, the left ventricle has to fight against unnecessarily high resistance with every heartbeat. In order to be able to perform this extra work, the heart muscle thickens steadily.

Symptoms

At a certain point, the system becomes unbalanced and the mass of the muscle can no longer be adequately supplied with oxygen-rich blood by the existing coronary arteries. The inner layer of the muscle suffers from oxygen deprivation, and the heart muscle loses strength and endurance. Symptoms such as palpitations, heart pain, fatigue, or loss of consciousness can now occur, especially during exertion.

Depending on the severity of the narrowing, the effect on the circulation, especially during exertion, can sooner or later lead to symptoms similar to those of aortic valve disease, including heart failure or sudden cardiac death.

Newborns born with severe subaortic stenosis are in a critical condition shortly after birth and require urgent surgery. The burden on the heart must be relieved immediately before heart failure with organ damage occurs. Often, there is narrowing of several sections of the left ventricular outflow tract, which must be surgically widened. However, many children have mild narrowing and only develop symptoms later in life. As a rule, therefore, lifelong monitoring of the findings and symptoms is necessary.

If there are signs of an increase in stenosis, lack of development, or reduced exercise capacity, a step-by-step approach is usually initiated. As long as the narrowing is not severe, drug treatment can reduce the strain on the heart and improve symptoms.

Therapy

During the operation, the narrowing below the aortic valve is removed. With the aid of a heart-lung machine and after opening the aorta, the constricting connective tissue and muscle are excised, thereby creating a wide outflow tract. Additional muscle bridges or non-functional tendon strands of the mitral valve must also be removed to reduce turbulence in the blood flow and thus reduce the likelihood of subaortic stenosis recurring.

If the narrowing and thus the strain on the heart increases again (expected in 10 to 15% of cases), it may be necessary to surgically remove the narrowing again.

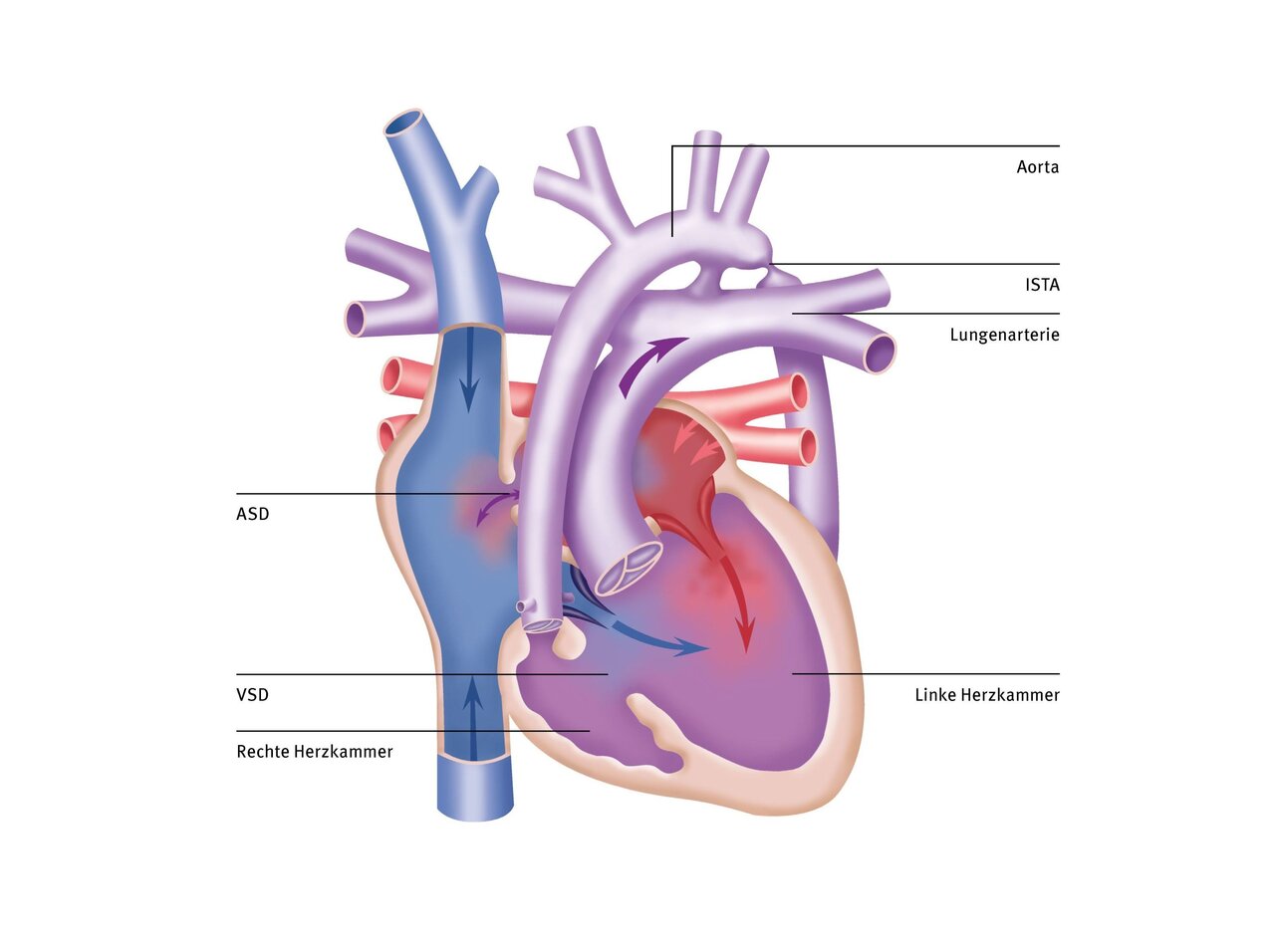

In cases of severe tunnel-shaped narrowing of the left outflow tract, but with a sufficiently large aortic valve, the modified Konno procedure is performed. In this procedure, the outflow tract of the right ventricle is used as access to the left outflow tract. To understand the surgical procedure, it is important to know that the anterior portion of the outflow tract of the left ventricle is formed by the interventricular septum, which, like the ventricle itself, is thickened in subaortic stenosis. In the modified Konno procedure, this portion of the septum is excised in the area of the outflow tract, thereby greatly widening it. The defect created by the excision is closed with a patch.

The Ross-Konno procedure is used when there is a combination of long-distance narrowing in the outflow tract below the aortic valve and an additional aortic valve that is too small.

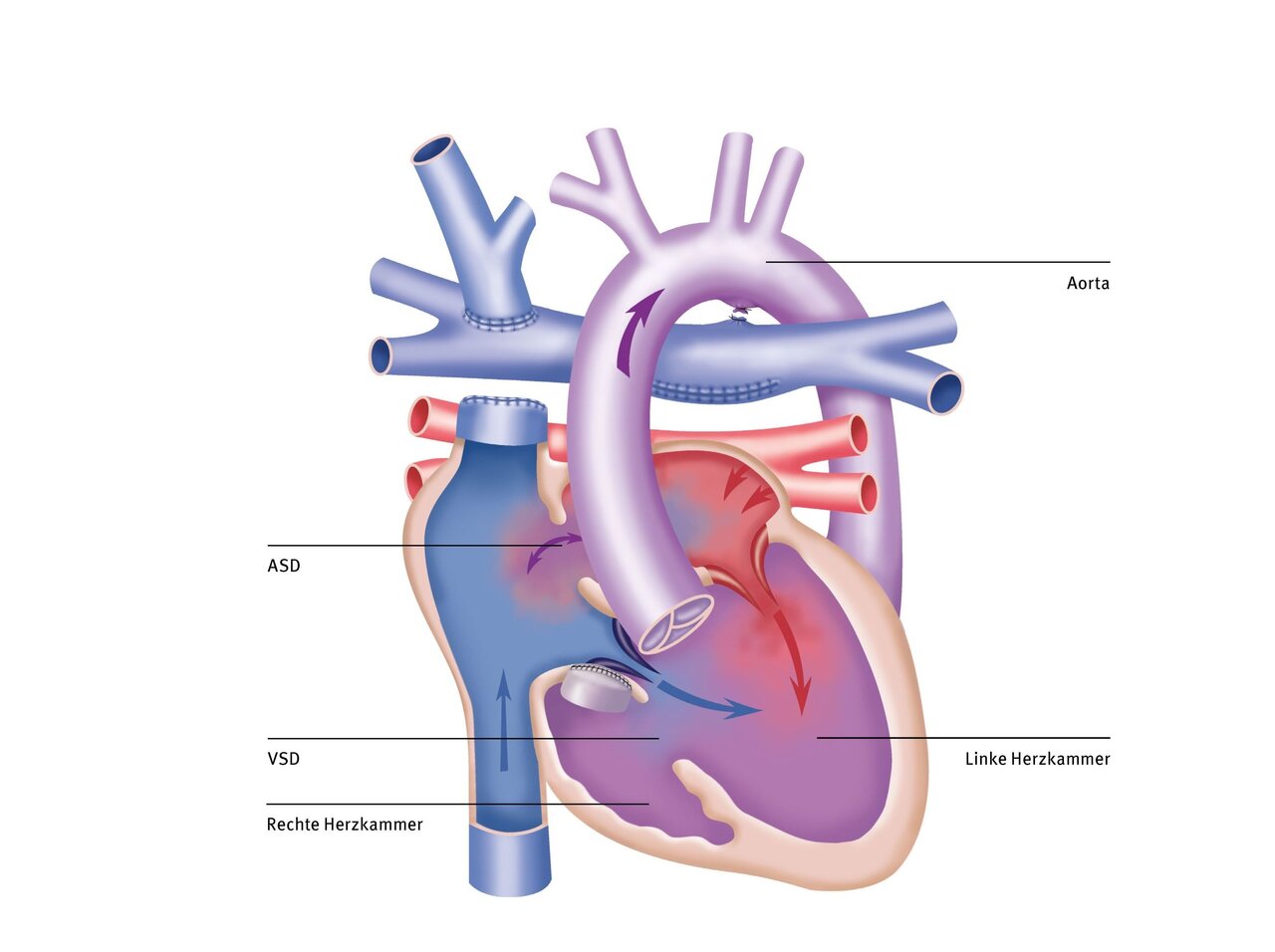

In Ross-Konno surgery, the patient's own pulmonary valve is removed and used to replace the aortic valve (also called an autograft, meaning that the valve material comes from the patient's own body). To do this, the diseased tissue of the aortic valve is completely removed. The ventricular septum is then incised in the area of the narrowing in the outflow tract (Konno incision) and the constricting connective tissue and thickened muscle are also removed. The patient's own pulmonary valve is then sutured into the aortic position. A biological prosthesis is inserted to replace the patient's own pulmonary valve, which is now missing.

We see the advantage of this extensive operation, particularly in children and young adults, in the preservation of the growth potential of the patient's own aortic valve and in the very effective elimination of severe tunnel-shaped stenoses of the entire left outflow tract. It also avoids the need to take blood-thinning medication.

Disadvantages include the limited durability of the replaced pulmonary valve (usually 5 to 15 years for biological prostheses) and the possibility of changes occurring later in the new aortic valve (autograft). Depending on preoperative risk factors, age, and the surgical technique used, the autograft may fail after 10 to 20 years, making it necessary to replace the aortic valve with a mechanical valve prosthesis.

Therapy at the German Heart Center at Charité

At our clinic, the Ross or Ross-Konno procedure involves suturing the patient's own pulmonary valve (known as an autograft) into the existing aortic root. In contrast, many other clinics remove the entire aortic wall and root and suture the pulmonary valve directly into the outflow tract of the heart.

Our method preserves the natural support function of the aortic wall. This reduces the risk of the new valve expanding later on. As a result, repeat procedures (reinterventions) can often be avoided or at least significantly delayed. This procedure can be used in infants, adolescents, and adults.

The routine use of our heart-lung machine with the world's smallest filling volume enables us to perform surgery without foreign blood transfusions in the majority of cases, even in newborns, which has considerable advantages. This not only minimizes the risks of infection and intolerance, but also often enables our young patients to recover more quickly after surgery. Most patients can be extubated very early postoperatively (fast-track concept) and thus recover quickly from the operation. Further information can be found in our externally validated quality assurance standards and annual quality reports.

Forecast

Regular and lifelong check-ups by a pediatric cardiologist specializing in the treatment of patients with congenital heart defects are necessary. Depending on the surgical procedure used and any residual findings, medication may also be necessary in the first few months after surgery upon discharge.

Long-term results show that normal development can generally be expected. Exercise capacity may be normal in patients with mild to moderate findings.

Depending on the severity of the disease, life expectancy may be reduced. Reasons for this include possible complications such as increasing heart failure, the need for repeated operations, or the occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias.

In the long term, 80 to 90% of patients do not require further catheter interventions or surgery on the aortic valve. However, in the case of longer or more complicated narrowings, the risk of further interventions is significantly higher.

One advantage of the Ross procedure is that the patient's own pulmonary valve (autograft) grows with the body. In contrast, the artificial pulmonary valve that is implanted at the same time needs to be treated or replaced more often, especially if only a very small prosthesis could be implanted in small children. Adolescents and young adults are generally less frequently affected by this.