Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV)

A double outlet right ventricle (DORV) is a congenital heart defect in which both the pulmonary artery (PA) and the aorta originate predominantly from the right ventricle. There is also a defect in the ventricular septum (ventricular septal defect, VSD); and the large vessels, the aorta and PA, may originate from the right ventricle on the right or left side, in front of or next to each other. Furthermore, there may be narrowings (stenoses) of the right and left outflow tracts.

Variants

There are many different types of DORV, which cause very different symptoms in patients. Treatment must therefore be differentiated and tailored to the individual.

Before corrective surgery, the heart functions like a single-chamber heart. A key factor determining the urgency and timing of surgical treatment is the blood flow to the lungs. If this is impeded, e.g., by a narrowing of the pulmonary artery, infants may suffer from cyanosis shortly after birth and require rapid treatment to improve blood flow to the lungs.

If blood flow to the lungs is unimpeded, pulmonary congestion may necessitate treatment even in the first few months of life. If blood flow to the lungs is approximately equal to blood flow to the body (balanced), the corrective surgery is usually performed between the fourth and sixth month of life.

There are different types of DORV, and the complexity of the corrective surgery varies accordingly:

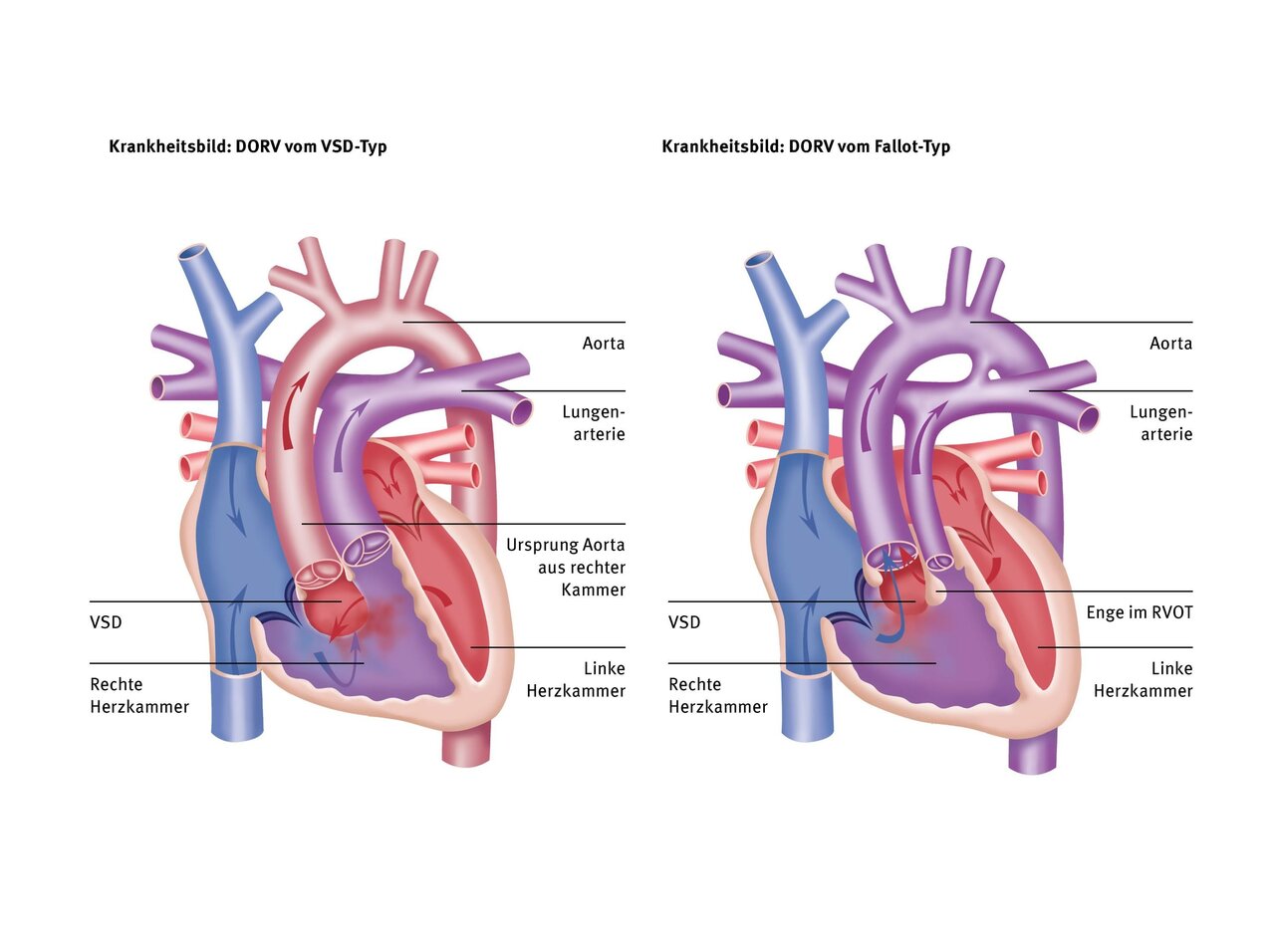

In this type, 100% of the pulmonary artery and slightly more than 50% of the aorta originate from the right ventricle. The VSD is located close to the aortic valve, as in a “normal” VSD without narrowing of the pulmonary artery. The flow of blood from left to right via the VSD can therefore lead to pulmonary congestion, as in VSD.

In this type, the vessels are similar to those in DORV of the VSD type. However, there is a narrowing of the right outflow tract or pulmonary artery valve, which restricts the flow through the VSD into the lungs. This type therefore does not result in pulmonary congestion. However, the reduced flow to the lungs can lead to oxygen deficiency/cyanosis if the right outflow tract is severely narrowed, similar to tetralogy of Fallot (TOF).

In this type, the pulmonary artery and aorta are reversed, as in a normal transposition of the great arteries (TGA). This results in 100% of the aorta and less than 50% of the pulmonary artery originating from the right ventricle. The VSD is therefore located below the pulmonary valve. There may be narrowing in the right outflow tract, which can lead to reduced growth of the aorta and aortic arch. Blood flow to the lungs is unobstructed, which can lead to pulmonary congestion.

This special form of DORV is similar to the TGA type, but the two large vessels are not located at the front and rear, but side by side, with the aorta further to the right and the pulmonary artery further to the left, riding above the VSD. Unlike in the TGA type, the VSD is located far in the outflow tract of the right ventricle. The aorta originates 100% from the right ventricle and there is often a narrowing below the aortic valve, which can lead to the ascending aorta and aortic arch being narrow (hypoplastic) and also needing to be widened during corrective surgery. In Taussig-Bing heart disease, pulmonary congestion and, at the same time, low flow into the aorta may occur.

In this type, which is also the most complex type in the DORV spectrum, both large vessels originate 100% from the right ventricle, which is why we also refer to this type as “200% DORV.” The VSD is a so-called “non-committed VSD,” which means that it is not associated with any large vessel but is located far away from it. This usually makes correction more difficult because the tunnel in the right ventricle from the VSD to the aorta is usually long and must be created in such a way that there are no narrowings in the area of the right inflow or outflow tract.

Symptoms

Depending on the type of DORV and depending on the size and location of the VSD, as well as any narrowing of the right outflow tract, different symptoms may occur at different times.

In VSD-type DORV, the increased blood flow through the VSD from left to right leads to pulmonary congestion if this is not “protected” by an additional narrowing of the right outflow tract. This can manifest itself in sweating, difficulty drinking, increased respiratory infections, and failure to thrive.

In Fallot-type DORV, on the other hand, similar to tetralogy of Fallot, depending on the severity of the narrowing of the right outflow tract, there is poorer blood flow to the lungs. The blood is therefore no longer 100% oxygenated, but is less enriched with oxygen. This lower oxygen saturation (e.g., only 75%) manifests itself as a blue discoloration of the skin (cyanosis), which is most noticeable on the lips of children.

In TGA-type DORV, the two “swapped” large vessels and the VSD located below the pulmonary valve result in a combination of pulmonary congestion, as blood is directed from left to right directly through the VSD into the overlying pulmonary artery. At the same time, cyanosis occurs in the body because the aorta, which originates entirely from the right ventricle, carries blood that is relatively low in oxygen. This leads to signs of heart failure, i.e., limited exercise capacity and, at the same time, blue discoloration of the skin.

Causes and risk factors

The cause of DORV, which accounts for about 3% of all congenital heart defects, is not yet fully understood. In most cases, it is a combination of different factors that contribute to the development of this heart defect.

In the womb, this heart defect causes a malformation of the common structure of the two large vessels, the pulmonary artery and the aorta, which, unlike in a normal heart, are positioned incorrectly and thus originate largely from the right ventricle. In addition, a hole (VSD) remains between the two ventricles, which closes during normal development in the womb.

Diagnosis

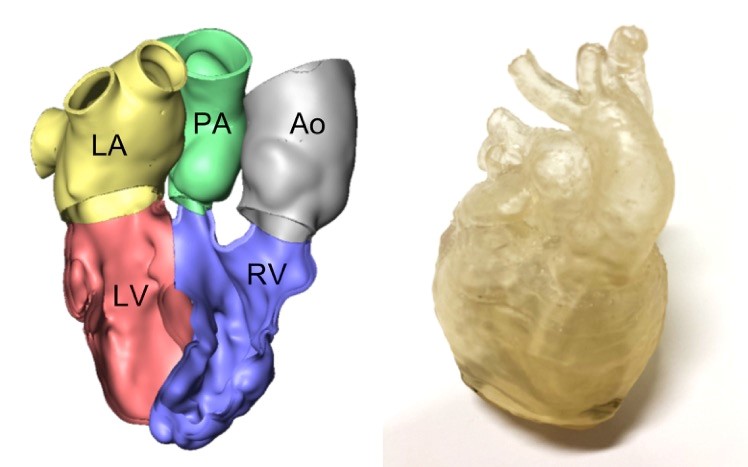

DORV can often be diagnosed prenatally using high-resolution ultrasound. After birth, an ultrasound examination of the heart is often sufficient for diagnosis. For surgical planning, a CT scan and the creation of heart models are very helpful for better recognition of the positional relationship of the VSD and the large vessels. If the anatomy of the coronary arteries is unclear, a cardiac catheterization may also be necessary.

Computed tomography (CT) can help to plan the operation precisely. This examination allows the positional relationship between the VSD and the large vessels to be visualized.

Therapy and timing of corrective surgery

Depending on the type of VSD, patients have different symptoms that can occur at different times. This determines when surgery is recommended and the technique used for correction.

If there is no narrowing in the right outflow tract, the symptoms that the child develops depend on the size of the VSD. If it is large, pulmonary congestion occurs early on (VSD-type DORV). In this case, similar to “normal” VSD, corrective surgery must be performed at the age of four to six months to prevent irreversible pulmonary hypertension from developing.

If, on the other hand, there is a narrowing of the right outflow tract, the lungs are initially “protected” from this flooding, but on the other hand, if the narrowing is severe, it can also lead to insufficient blood flow to the lungs and thus to cyanosis (Fallot-type DORV). If the right ventricular outflow tract is severely narrowed, cyanosis may be observed early after birth, sometimes requiring palliative surgery in the form of a surgically created shunt or catheter intervention with a ductus stent to supply the lungs with sufficient blood before a definitive correction can be performed.

If there is a so-called “DORV of the TGA type,” i.e., transposition of the great vessels and a VSD below the pulmonary valve, pronounced signs of heart failure and cyanosis occur shortly after birth, which is why correction is indicated already in the neonatal period.

There are medicinal and catheter-based treatment options that can be used to alleviate symptoms and buy time, but surgical correction of the DORV is necessary in all cases. This varies depending on the type of DORV present:

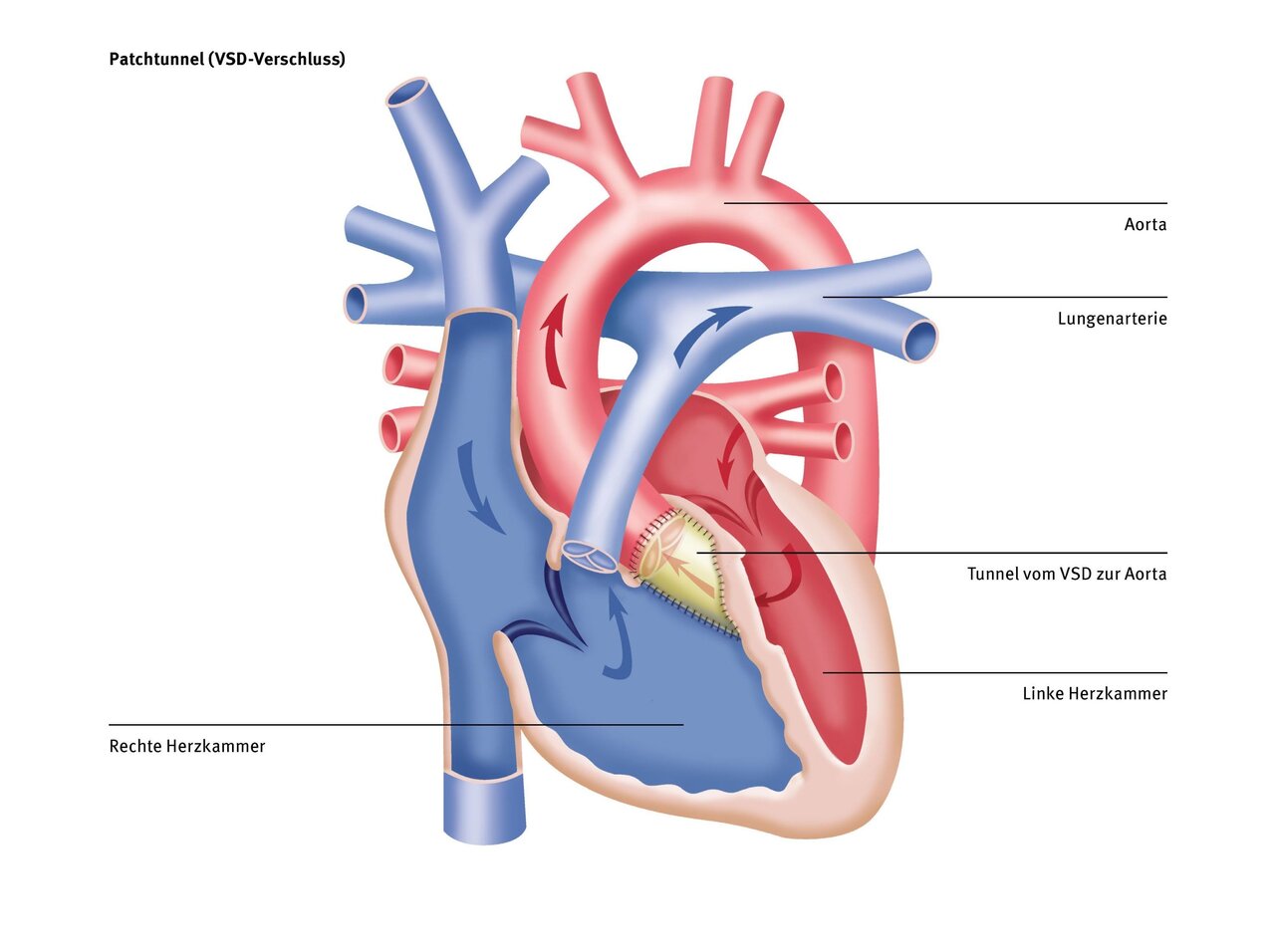

With this type of DORV, similar to a “normal” VSD, a patch from the patient's own pericardium is used to close the hole at the ventricular septum level and at the same time create a connection from the left ventricle to the aorta and from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery, which should be as straight as possible and without any narrowings. To achieve this, it is sometimes necessary to enlarge the VSD in order to create a “tunnel” in the heart that is as straight as possible and free of narrowings.

With this type of DORV, the type of surgical procedure varies depending on the severity of the narrowing in the right outflow tract. If the stenosis is so severe that it causes cyanosis in the newborn, a palliative procedure in the form of a shunt between the pulmonary artery and the aorta or the first vessel branching off from the aorta (subclavian artery) may be necessary to ensure sufficient blood flow to the child's lungs until a definitive correction can be performed. This should be performed at a minimum age of three to four months and a body weight of less than 5 kg.

The correction consists of closing the VSD with a patch made from the patient's own pericardium. Here, too, it is particularly important to create a straight and narrowing-free “tunnel” in the heart that connects the left ventricle to the aorta. Depending on the severity of the narrowing of the right outflow tract, the thickened muscle tissue must then be removed below the pulmonary valve and/or the pulmonary valve must be repaired. This is often possible by loosening the adhesions/sticking of the valve pockets or by widening the valve ring (commissurotomy, valve-sparing technique, transannular patch; see correction of tetralogy of Fallot).

If, despite all these methods, it is not possible to preserve the valve, for example in the case of pulmonary valve atresia, a so-called “RV-PA conduit” is used. This is a small tube made of plastic “PTFE” or a biological prosthesis that creates a connection between the right ventricle and the pulmonary arteries.

With this type, correction is necessary as early as the newborn stage. This consists of “swapping” the two large vessels through a so-called “switch operation” and then connecting the left ventricle to the aorta and the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery through VSD closure. In this case, too, it is particularly important to create a straight and narrowing-free “tunnel” in the heart that connects the left ventricle to the aorta. If there is a narrowing in the pulmonary valve area (DORV-TGA + pulmonary stenosis) in TGA-type DORV, the German Heart Center at Charité performs what is known as “en bloc rotation of the great vessels.” For more information, see the chapter on TGA.

As mentioned above, a straight, narrowing-free “tunnel” in the heart is essential for a “two-chamber correction,” i.e., a correction that creates two separate circulatory systems, for the long-term prognosis. If this is not possible despite enlargement of the VSD, e.g., by a valve support device extending into the outflow tract, then in some cases “univentricular palliation,” i.e., the creation of a “single-chamber heart,” is a reasonable option (see “Univentricular reconstruction”).

Therapy at the DHZC

At the German Heart Center at Charité, we have set ourselves the goal of finding the best possible surgical treatment option for each patient. This means that our team of pediatric heart surgeons and pediatric cardiologists carefully analyze each patient and their heart anatomy in order to make the best decision for them. We always strive to create a “biventricular correction,” i.e., a “two-chamber heart,” as studies have shown this to be more ‘physiological’ than a “single-chamber heart” reconstruction. Unfortunately, this is not possible for every DORV heart, but it is possible for many.

In particularly complex cases where normal echocardiography is not sufficient, we use MRI or CT examinations. These imaging techniques enable us to use special programs to produce a 3D print of your child's heart, allowing us to make the most accurate decision possible regarding the optimal surgical treatment. This has already helped us to greatly improve the outcome for patients in many cases.

Examples of 3D-reconstructed hearts of DORV patients with complex anatomy.

On the left: the reconstructed model on the computer.

On the right: the printed model for better visualization.

Forecast

Depending on the actual operation performed, your child will be able to resume normal activities after varying recovery times in most cases.

If a shunt must first be inserted as a “palliative measure” until complete correction is possible, the oxygen saturation in the blood must be closely monitored during this time. It may be necessary for the child to remain in the hospital during this time until the definitive correction can be performed so that they can be closely monitored and cared for.

If a definitive correction is possible, we assume that the child will be able to resume normal physical activity after their hospital stay and a corresponding recovery period. However, in the weeks, months, and even years following the operation, regular check-ups with a pediatric cardiologist must be carried out in order to closely monitor the child's further development and immediately detect any narrowing of the outflow tracts.

The sternum, which we have to cut lengthwise during this operation, usually takes about four to six weeks to heal completely and become stable. After that, there is nothing to prevent normal physical activity.

Questions and answers for parents (FAQ)

Depending on the actual operation performed, different postoperative follow-up care is necessary. In any case, lifelong echocardiographic checks should be performed by a pediatrician after DORV correction in order to detect any narrowing in the right, or more rarely the left, outflow tract, an RV-PA conduit that has become too small, or leaks in the aortic valve after a “switch operation” has been performed.

Your child's quality of life and life expectancy will vary depending on the actual operation performed.

After complete correction, quality of life should not be significantly restricted, apart from regular check-ups with a pediatric cardiologist. However, if narrowing occurs in the right outflow tract over time, this can reduce quality of life, which is why accurate and close monitoring is important.

There has been significant progress in recent years in terms of survival after DORV correction. The 15-year survival rate for all types of DORV combined is around 80%, and for some types, such as VSD or Fallot-type DORV, it is even over 95%.

Whether further interventions or operations are necessary depends very much on the existing anatomy and on the operation that was possible due to the anatomical conditions. It is important that the “tunnel” in the heart, which connects the left ventricle to the aorta, is as straight and free of narrowings as possible. If it is rather “winding” or already prone to narrowing at the time of surgery, further interventions or operations in the area of the right outflow tract are more likely.

Narrowing of the left outflow tract, on the other hand, is less common, but can occur if tension arises in the area of the “tunnel.” If the pulmonary artery valve had to be enlarged by means of a so-called patch plasty due to its small size, further surgery on this valve may be necessary, as the valve ring has only limited growth potential due to the enlargement plasty. Especially if an “RV-PA” conduit was used, replacement with a larger or valve-bearing conduit is necessary.

If a switch operation was performed for TGA-type DORV, leaks may occur in the neo-aortic valve, which may necessitate reoperation. Therefore, regular echocardiographic check-ups with a pediatric cardiologist are necessary.