Atrial septal defect (ASD)

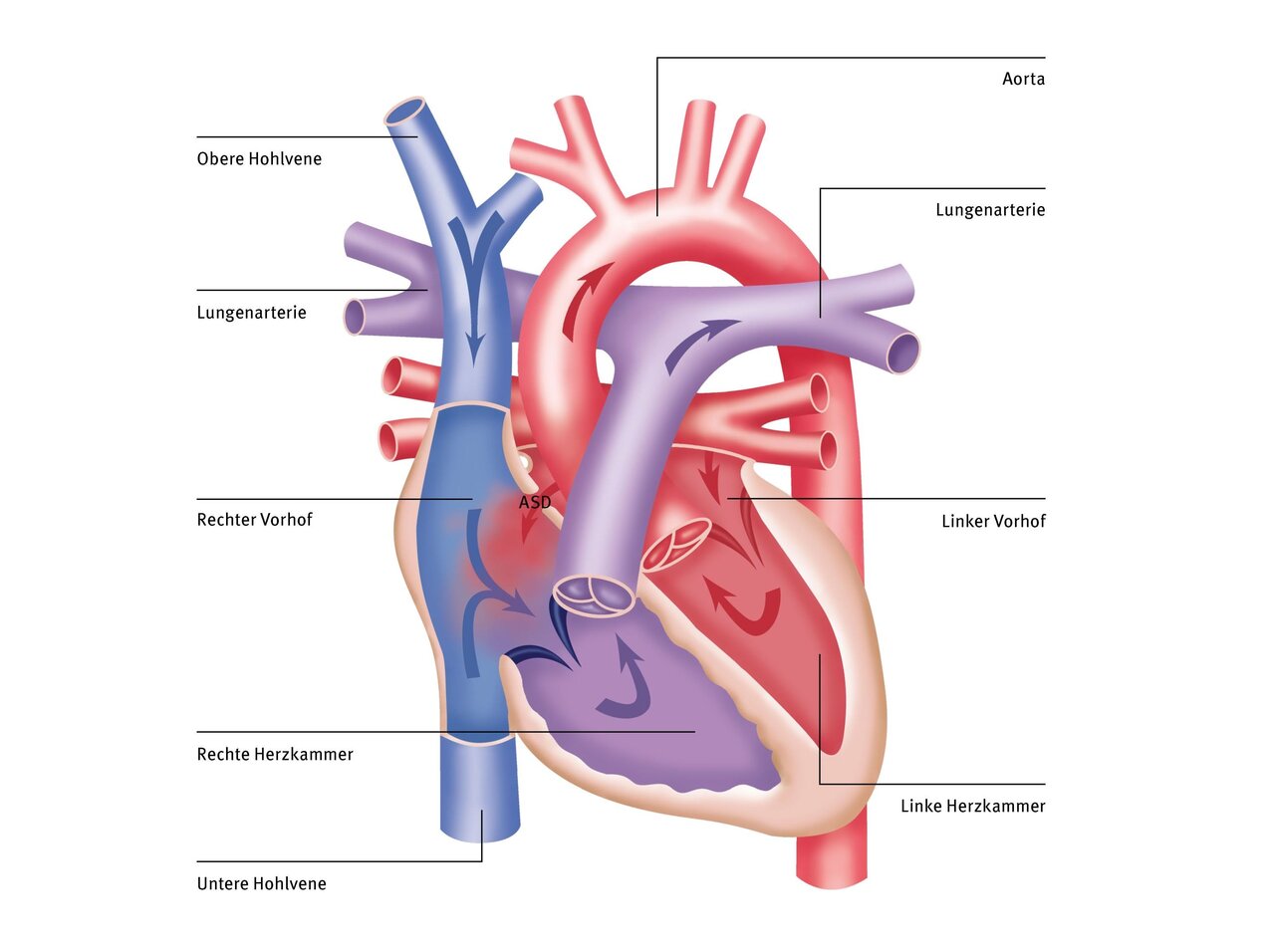

Atrial septal defects (ASD) are the second most common congenital heart defects. They are characterised by a defect (hole) in the septum of the ventricles (atria), which separates the left atrium from the right atrium. As a result, blood leaks from the left atrium into the right atrium. As this blood then passes back into the pulmonary circulation via the right atrium and the right ventricle and then back into the left atrium, it ultimately circulates as a ‘short circuit’ and is missing from the blood supply to the systemic circulation. It leads to an increased load on the right ventricle and can also become noticeable in the form of cardiac insufficiency due to the reduced cardiac output for the systemic circulation, particularly in the case of large defects.

Most ASDs remain asymptomatic for a long time, as the additional load caused by the short-circuit flow is often well tolerated for a long time. ASD is therefore most frequently discovered as an incidental finding during a routine check-up due to a heart murmur. It is therefore also the most common newly discovered congenital heart defect in adults.

Origin

Every baby initially has a hole in the septum between the atria. In the womb, the hole is necessary so that the blood can pass from the right atrium to the left atrium without flowing through the lungs. After birth, when breathing begins, this connection between the atria is no longer needed and closes on its own or becomes very small. Sometimes the hole is larger than normal and does not close on its own.

In some children, the cardiac septum between the two atria has not developed properly, so that connections remain. Depending on where the hole is located, other malformations may also be associated with it, such as a malformation of the pulmonary veins or a cleft in the mitral valve. An ASD can also occur in conjunction with other heart defects.

Normally, the right heart, i.e. the right atrium and right ventricle, pumps blood into the pulmonary circulation and the left heart, i.e. the left atrium and left ventricle, pumps blood into the systemic circulation. If there is an ASD, blood flows from the left heart into the right heart and the right heart and lungs are put under greater strain by the additional blood. If left untreated, the right heart and pulmonary vessels can be permanently damaged. However, if the ASD is very small, there may be no problems or symptoms. Many adults have a very small hole between the atria called a PFO (persistent foramen ovale).

Differentiation

The atrial septum develops from two different parts, the so-called ‘primum septum’ and the ‘secundum septum’, which grow together to form a common atrial septum. Depending on the localisation of the defect, different types of ASD are therefore distinguished. This is particularly important for the treatment options.

The following types of atrial septal defect can be distinguished:

- Secundum type (ASD II)

- Primum type (ASD I)

- Sinus venosus type

- Coronary sinus type

- Persistent foramen ovale (PFO)

Symptoms

Typical symptoms include frequent respiratory infections or reduced resilience. In the case of very large defects, infants may also have difficulty drinking, reduced weight gain or laboured breathing. However, children with an ASD often have no symptoms at first, but are noticed by the paediatrician due to a conspicuous heart murmur. However, if there are signs of strain on the right heart, the defect should be closed in good time in order to avoid long-term consequences. These include cardiac arrhythmia as well as the development of pulmonary hypertension. However, if a defect is very small and there are no signs of strain on the right heart, it does not necessarily have to be closed.

Diagnosis

Careful physical examination and echocardiography (cardiac ultrasound) are the main examination methods used to diagnose an ASD and to decide whether and when an ASD should be closed. The size of the defect and the strain on the heart are the main factors in deciding whether closure is necessary and when.

In special cases with special questions, such as in the presence of an ASD I or an SVD, or in adults with limited sound conditions, a transoesophageal echocardiography (‘swallowing ultrasound’) and/or a cardiac MRI examination (magnetic resonance imaging) may be necessary, which are also performed at the DHZC. In rare cases, e.g. if there is also a suspicion of pulmonary hypertension or a dysfunction of the left ventricle, a cardiac catheterisation may also be necessary before a decision is made on treatment options.

As a rule, an electrocardiogram (ECG) and/or a long-term ECG is also carried out to rule out cardiac arrhythmia.

Therapy atrial septal defect of the secundum type (ASD II)

The ASD of the secundum type (ASD II) accounts for the largest proportion of isolated atrial septal defects at approx. 80%. Smaller defects (<10mm diameter) show a certain rate of spontaneous occlusion in infancy, so that it is worth waiting here. In the case of relevant permanent defects, closure is usually recommended at pre-school age. However, in the case of very large defects or pronounced stress on the heart, this may also be necessary earlier, in infancy.

For the treatment of ASD II, minimally invasive umbrella closure using cardiac catheterisation is now the gentle standard therapy. In most cases, this is performed as standard at the DHZC without the use of X-rays, using only transoesophageal echocardiography (‘swallowing ultrasound’). The vast majority of ASD IIs can be successfully closed using an implantable umbrella during cardiac catheterisation. In some cases, e.g. smaller children with large defects or very unfavourable margins, an umbrella closure is not possible and surgical closure is required (see below).

Therapy Atrial septal defect of the primum type (ASD I)

In atrial septal defect of the primum type (ASD I), the defect is located in the lower part of the atrial septum, in the area of the valves that lie between the atria and the main chambers (AV valves). For this reason, an umbrella closure is not possible, as there is no retaining edge to the valves and the valves would be disrupted as a result. Spontaneous occlusion is not to be expected. ASD I must therefore be surgically closed. It is not uncommon for the malformation of the primum septum to also affect some of the AV valves due to cleft formation, so that these can exhibit significant leakage, which must then also be corrected.

During the operation, the right atrium is opened using the heart-lung machine (HLM) and the left atrioventricular valve (mitral valve) is corrected first. The hole in the atrium is then closed with a patch. The sutures can also be placed at the upper edge of the ventricular septum if there is a small ventricular septal defect, which can then be closed directly.

The heart defect is then completely corrected. In rare cases, a leak in the mitral valve may remain if it was also affected. Depending on the location and size of the defect, the need for concomitant surgery on the AV valve and the age of the patient, the operation can be performed via a cosmetically favourable access route via the side of the chest (lateral thoracotomy), which is performed as standard at the DHZC.